By Nicolas Fonty and Barbara Brayshay

Introduction

In the London and Paris metropolises, coalitions are forming to promote and enable community-led planning and other community-led initiatives. For organising their network under construction, they are in demand for digital platforms, particularly cartographic ones to use as tools for community participation, place making and information gathering.

In parallel with these developing coalitions there are, in these two urban areas, many different groups working on civic mapping projects.[1] Typically each one is particular in their technical approach, focus and territorial scope. The aim of most of these civic mappers is to engage with wide audiences, ideally with all of the citizens in their target territories. However the reach and scope of each project remains, in many cases relatively limited. It seems therefore that there is great potential to explore the possibilities for convergence between the demand for networking tools by communities and supply from civic activists.

In both cities there are already networks emerging. For example in Paris, digital platform designers are now cooperating with varying degrees of connectedness. However this ‘bubble’ of digitally skilled civic mappers is isolated from other ‘bubbles’ of mappers –for example, groups that are looking for innovative devices to directly engage citizen participation in public spaces.

What then is the future of this nebula of emerging cartographies? Will they succeed in cooperating enough to work with the metropolitan coalitions that are under construction and reach the general public? And in what form? Will they come together under a single platform in the way ‘winner takes all’? Or will they specialize around specific approaches and articulate themselves within a balanced ecosystem?

Metropolitan coalitions for community-led planning

There are networks under construction in London and Paris that are working to federate the various local groups who are committed to community-led planning. That is to say, planning based on citizens expertise, exploring alternatives to top-down processes from the market or public authorities, defending genuine inclusion and social justice, or promoting cooperation and the common management of local resources.

In London, the Just Space network, https://justspace.org.uk/, includes major national networks as well as those with a specifically London focus, including the London Federation of Tenants, London Citizens Growing, Ubele Initiative for the African diaspora, GMB London and dozens of community groups involved in regeneration, planning or citizenship issues, as well as a large number of activists, practitioners or researchers committed to community-led planning. Bringing together communities of place, interest and identity. The primary objective of Just Space currently is to give voice to grassroots Londoners in debates on metropolitan planning and in particular on the formulation of the Mayor’s London Plan [2] a spatial development strategy for the future of Greater London, facilitating and amplifying each other’s voices.

In France, the APPUii network (Alternatives Pour des Projets Urbains Ici et à l’International), https://appuii.wordpress.com/, is also working to federate a national network of actors, mobilizing their skills for urban transformations that correspond to the demands of residents. In particular, it supports community groups in working class neighbourhoods seeking participatory alternatives to the demolition-and reconstruction of their estates. This network includes academics and students, including Paris 8 and 10 universities, Maison des Sciences de l’Homme (MSH), city making professionals, community activists (including Coordination National du Logement /CNL or Droit Au Logement /DAL-HLM which focus on housing) and community groups from working-class neighbourhoods including the Pas Sans Nous (Not Without Us) national coalition. APPUii’s ambition ultimately is a national movement but currently its action is mostly focused on the Paris metropolis because of the location of its main actors.

It is very interesting to note that these two networks, Just Space and APPUII, in addition to interlinking at local, metropolitan and national scales, they are also seeking to align themselves with other international networks. To meet this goal Just Space and Appuii are now participating in collaborative seminars and common events, exchanging their respective experiences and knowledge.

Two Coalitions in Demand for Digital Platforms

Just Space and Appuii are still under construction. The London network is a little more mature. Having emerged in 2006, it has gradually strengthened since. Appuii made its first steps a little later in 2009 and is clearly now in a phase of expansion since its official foundation in 2012. These hybrid alliances (diversity of actor types), informal (no real charter) and multi-scalar (mixing networks, institutions, groups and individuals) seem to have reached a critical size that requires the development of collective digital tools. They are at once too big to avoid having internal tools to strengthen cooperation and share knowledge, yet they are still not big enough to stop growing, joining other allied networks and opening up to a wider audience by making themselves visible digitally. It is primarily a lack of financial resources that is delaying the creation of appropriate platforms. However some progress is being made as discussions are now beginning to take place: firstly to define the objectives and challenges of these tools, and secondly to identify the skills and knowledge that should be committed to this end.

In the following, we define the objectives of an ideal platform and the skills that would be essential to bring together for its creation.

Three objectives and challenges:

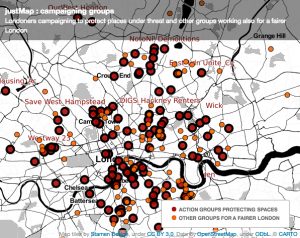

1. A primary objective is to make visible through interactive cartographies the network of the coalition (in this case Just Space or Appuii), but also the extended network of other groups that share similar approaches. It is very instructive internally for each individual or group to know the complex networks in which they belong. And it is also important to contextualise one’s own actions (that might seem modest or isolated) by placing them in a much more powerful framework.

Externally, the network map is a visual communication document that has impact, for example with a) public authorities who may reconsider their attitude towards a local collective if it is aggregated in one of these metropolitan coalitions and b) with local groups which may not be aware of this collective approach and would like to join it. The map then acts as a banner that federates internally and empowers externally.

Figure 1. Concept mapping of the Just Space extended network.

Link to the poster: http://n.fonty.free.fr/JustMap/London/JustMap_clusters_A1.pdf

Link to the interactive map: https://kumu.io/nicolas/justmap#campaignstopics/action-area-2

Link to the dataset: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1XgNo5HWIOtj99TYQhVcTvR3NBIDTuQ0DIIvCnyIMhUM/edit

In addition to the network (its actors, its campaigns and projects, its objectives and issues, and its next actions) it is also important to make visible the data that underpins the approach of community-led planning. Mapping injustices, social disparities, environmental problems, cases of corruption related to planning and mapping in parallel the commons or resources such as physical resources (buildings, landmarks, public spaces, street furniture); together with human resources such as community or action groups, institutions, businesses of interest, neighbourhood festivals and events, and also the less tangible networks of social infrastructure that have local value, as well as alternatives and actions that emerge.

Figure 2. Geographic mapping of the Just Space extended network

Link to the interactive map: https://justplace.carto.com/viz/ecb99910-24e7-4467-a068-3a1f496d1b93/embed_map

Link to other geographic visualisations: http://justplace-london.blogspot.co.uk/p/map-visualisations.html

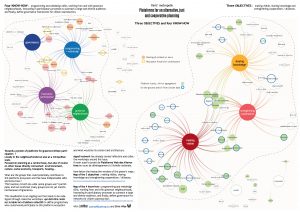

2. A second objective of this ideal platform is to facilitate the sharing of knowledge and information using a wiki mode of collaboration. Content could include legal and technical information relating to issues such as planning, housing, environment and local economy. As well as a section dedicated to public participation such as communication advice and examples of public events, plus a library of case studies of successful campaigns and information about current actions and activities.

3. The third objective is to create a tool for cooperation between members: offering channels for discussion and collaborative decision-making tools, disseminating news on topics related to community-led planning and ongoing campaigns, and also sharing a calendar of events that may interest the network.

Four skills and know-how:

Four complementary skills that are necessary for the design of this ideal platform:

1. #CODE: For creating this set of digital tools and working towards interoperability with other platforms and datasets.

2. #GOVERNANCE: How is this platform managed collectively? How is it moderated, animated, updated? Is a charter necessary? What is a digital commons? How to combine physical governance of the network and digital governance of the platform?

3. #PARTICIPATION+: What innovative, inclusive, creative and attractive processes for reaching a wide audience? How to couple digital processes to physical interfaces (workshops, demonstrations, games, events) for being present physically in public spaces?

4. #GRASS-ROOTS ENGAGEMENT: How to address the issues of grassroots or working class areas and work in close collaboration with its inhabitants? How to create tools that reach beyond the educated middle classes?

If the first two skills, #code and #governance seem quite obvious, the other two skills of #participation+ and #grassroots engagement are also necessary. Previous research shows that participative process are rarely inclusive, particularly in terms of digital citizen participation where contributors are predominantly male, graduates and aged between 25 and 50 years (Haklay 2013, Duféal-Nouchet 2017)[3]. In order to widen participation it is therefore necessary to be creative in terms of creating opportunities for engagement, for instance by being present in public spaces to reach those who are digitally excluded. We must also strive to include the residents of working-class neighbourhoods in these processes if one of the community-led planning challenges is to promote inclusion and social justice or the right to the city for all.

The Landscape of Citizen Platforms at the Scale of the Paris Metropolis

If we now leave the theoretical framing of an ideal platform and look at the existing related approaches in Greater Paris, there are a surprising number of initiatives to be found. This first inventory, organized by linking the different approaches to the objectives and skills listed above, is currently an evolving ‘work in progress’. However, it does reflect the vitality of the research and development that is currently underway around the field of citizen platforms, as well as the diversity of actor types.

Figure 3. An ideal platform for community-led planning.

Link to A1 poster (English): http://n.fonty.free.fr/JustMap/Paris-metropolis/citizen_platforms-greater_Paris-A1_poster.pdf

Link to interactive map (French): https://kumu.io/nicolas/plateforme-alternatives-metropole-parisienne#objectifssavoir-faire

Link to datasets: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/182kQrJ0NONl5gUUUkgmFJqWhwtHEcP9smOSfkgj7RV8/edit

This first inventory reveals the ‘scattering’ of emerging projects and demonstrates the need to initiate cooperation between approaches that are either very similar or complementary, and the need to build stronger networking and links between ongoing projects. The mapping shows that a community of practice [4] of ‘civic platform makers’ is potentially under construction and this inventory is intended as a collective working tool for this potential community.

We now wish to focus on a subset of this nebula – the groups whose objective is #making visible, the civic mappers in this article.

Towards a Community of Practice of Civic Mappers of the Paris Metropolis

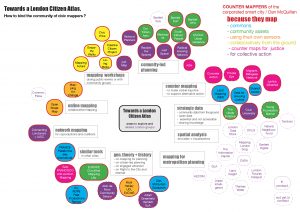

Figure 4. Ongoing inventory of the Paris metropolis Civic Mappers

Link to A1 poster (English): http://n.fonty.free.fr/JustMap/Paris-metropolis/Civic_mappers-what_cooperations-A1poster.pdf

Link to interactive map (French): https://kumu.io/nicolas/civic-mappers-paris-metropolis

Link to the dataset: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/182kQrJ0NONl5gUUUkgmFJqWhwtHEcP9smOSfkgj7RV8/edit

The more detailed inventory of civic mappers (Figure 4) whose work covers the territory of the Paris region provides some detail of the current situation and allows us to support three hypotheses:

A community of practice of civic mappers is under construction

Events and physical meeting places

MeetUp Carto Paris [5] has organised regular meetings and seminars since June 2015 (11 in total). Most of the speakers are interested in digital tools and their development (#code) but they also attract a few groups focused on other skills (#participation+ or #governance). Two other isolated events, related to MeetUp Carto, also brought together other actors from the same nebula: Digital Synergy of Alternatives (Synergie Numérique) in March 2017 and Millemont Makers & Music Festival in October 2017.[6]

The social movement Nuit Debout [7] in the spring of 2016, allowed many individuals or groups interested in citizen-led approaches to civic mapping or community-led planning to meet, discuss and sometimes cooperate. CartoDebout [8] is a project that was created on this occasion.

Online forums

Le chat des communs [9] includes several discussion channels including one for MeetUp Carto, another one for Synergie Numérique des Alternatives [10] and several for Communecter and PWA, two important projects discussed in more detail below.

Cooperative projects

Communecter: a local and civic societal network developed using open source software whose goal is to connect the various actors in a town, including institutions, citizens, community groups and local businesses. This platform aims to boost local democracy and solidarity projects in France by connecting actors through various social network tools, such as the creation of groups, dedicated forums, news feeds and customised calendars. It also includes cartographic visualizations which are frequently absent from other social networking platforms.

PWA for Plateforme Web des Alternatives: an ongoing project that automatically aggregates on a single map data from dozens of online maps listing alternatives in France.

Près de Chez Nous.fr: an online collaborative map born from the collaboration of Colibris, Communecter, Printemps de l’Education and Marché Citoyen to identify actors offering local products or services related to the social and solidarity economy and the protection of the environment.

An ecosystem model rather than a single platform

Even if this first inventory of civic mappers is incomplete, what begins to emerge from the data is the diversity of actors engaged in civic mapping, ranging from activist led sites such as Intersquat Paris, a resource for housing squatters to APUR, a municipal agency dedicated to inform planning authorities and key stakeholders in Greater Paris. There is also a diversity of methodologies with some groups focused on digital development and others on collaborative processes, and with a range of territorial scales of action (local, metropolitan, national). As we see above, the civic mappers are well aware that regroupings and collaborations must take place to widen the circle of the users of their platforms. However, given the diversity of actors, approaches and scales of action, it is difficult to see how a single platform model could be satisfactory for regrouping their activities.[11]

The ecosystem concept is more interesting in this context because it implies exchanges, dependencies and complementarities between the various components of the system to achieve a common goal. Julien Lecaille uses the metaphor of the archipelago which is just as interesting, suggesting that each platform is:

“ an island that makes its choices of governance, its economic model, its technological choices, its ontologies. However, some islands are “closer” to each other, because they share similar characteristics. Operating in an archipelago does not hinder the autonomy of each project but allows for joint action when there are enough similar characteristics identified.”[12]

The territory of the Community of Practice

Whether the notion of the ecosystem or archipelago is retained, both include the notion of a specific territory. Because the purpose is to design digital tools for community-led planning, these must adapt to the territories in which they are supposed to be used. This is the principle of the ecosystem model where organisms interact collectively with their environmental support. Civic platforms cannot be identical in Paris or London when cultural and historical environments, urban forms, social issues, regulations and forms of democracy are distinct. Similarly, the French Alps and the Paris metropolis, which are very distinct forms of territory, will obviously not have the same needs.

Finally, it is also vital for a community of practice to sometimes meet physically. Digital tools allow remote collaborations, but direct meetings or group workshops are essential moments of interaction. The community is therefore dependent on a spatial territory within which its members can meet without too much difficulty.

Each of these different ‘ecosystems’ are therefore specific to a particular spatial territory but they are obviously not isolated from each other. The scales are of course interdependent: local <regional <national <continental <international, and some topics are common between different territories. Inevitably there is an overlapping of communities of practices ecosystems. The inventory of civic mappers in the Paris metropolis illustrates this overlapping, with some focusing on a local territory (Saclay, La Marne) where as others have a metropolitan or national scope, and others such as Open Street Map operate at an international scale with national and regional sub-ecosystems organized into sub-communities of practice. An inventory of London civic mapping would show similar overlapping of scales and focus.

Figure 5. Inventory of the London Civic Mappers Ongoing work in parallel to the inventory of the Paris’s civic mappers

More information here: http://n.fonty.free.fr/JustMap/blog/lectures/DPU1_justMap-lecture_on_London_civic_mappers.pdf

Link – Paris Mappers Agenda: https://drive.google.com/open?id=11403Yl44K91E_aVQBxbkLGTk9xroviK4nx2bblWMBdM

Link – London Mappers Agenda – March 27th 2018: http://networkedcity.london/london/march27event

A call for participation in a seminar of workshops and panel discussion – London and Paris

As the inventory mapping shows there are communities of practice of metropolis’ civic mappers under construction both in Paris and London. It is important to organize events to strengthen them and in particular to reach wider audiences. The purpose of this article is to introduce two forthcoming seminars to collectively consider this issue.

In Paris, a collaborative document has just been initiated with some of the Paris civic mappers to develop the agenda and form of this upcoming meeting and everyone is obviously invited to contribute to this document: https://drive.google.com/open?id=11403Yl44K91E_aVQBxbkLGTk9xroviK4nx2bblWMBdM

In London, civic mappers are invited to a similar event that will take place on 27th March 2018 here is a link to the Invitation: http://networkedcity.london/london/march27event

It seems fundamental that civic maps are co-produced with those who could use them and who have no specific knowledge of cartography. The idea is to invite one or more groups of citizens during these meetings to confront issues of supply and demand raised in the introduction. These events will be an opportunity, for the various civic mappers present, to affirm common or complementary denominators (issues or objectives, skills or know-how, priorities, and future actions).

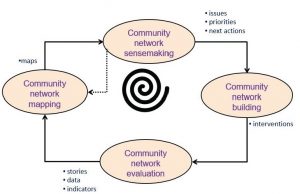

This approach directly references the work of Aldo de Moor (2017) [13] where he proposes an iterative process of mapping a community to gradually define collectively its issues, priorities and next actions. The community network mappings proposed here of the civic mappers of Paris and London aim to contribute to this goal. [14]

Figure 6. Aldo de Moor (2017): The Community Network Development

End notes

About the authors

Nicolas Fonty is a freelance architect /urban designer, independent researcher and autodidact mapper. Through research, activism, practice teaching and volunteer support, he has been involved in many civic mapping initiatives for community-led planning in London and Paris including justMap, http://justplace-london.blogspot.co.uk/, Occupy#PublicSpaces, http://www.occupy.fr/, and cartoDebout, http://cartodebout.blogspot.fr/. He is member of Civic Wise, https://civicwise.org/about/, an international network for civic design and worked on many urban design issues at metropolitan and local scales in Greater Paris, http://fonty.nicolas.free.fr/.

Barbara Brayshay is a Director of Living Maps, http://livingmaps.org.uk, a network of researchers, community activists and others with a common interest in the use of mapping for social change, public engagement and community campaigning and together with Nicolas Fonty edits the Wayponts section of Living Maps Review, a Journal dedicated to critical cartography and participative mapping. An independent researcher, her interests are in the areas of social justice, digital media, community development and sustainability.

Barbara and Nicolas work together developing the justMap platform and actively participate with numerous activist London networks to enable greater community empowerment.