by Em O’Sullivan

Over the past six years I’ve witnessed a growing awareness of issues of diversity and accessibility in the global maker movement. The lack of women, people of colour, people with disabilities, older adults, people with caring responsibilities, and people with low incomes has increasingly become part of the everyday conversations happening in makerspaces and at maker events, and maker communities are actively taking steps to become more inclusive.

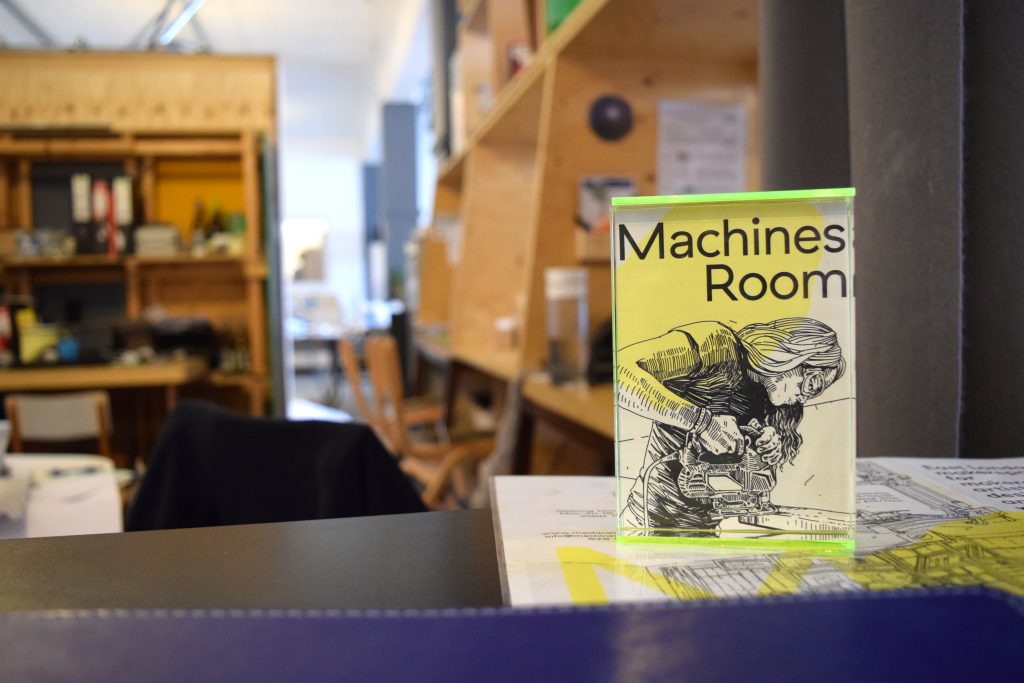

Figure 1. Machines Room in London, England has a high proportion of women staff and members. They make sure to place this front and center in their promotional material.

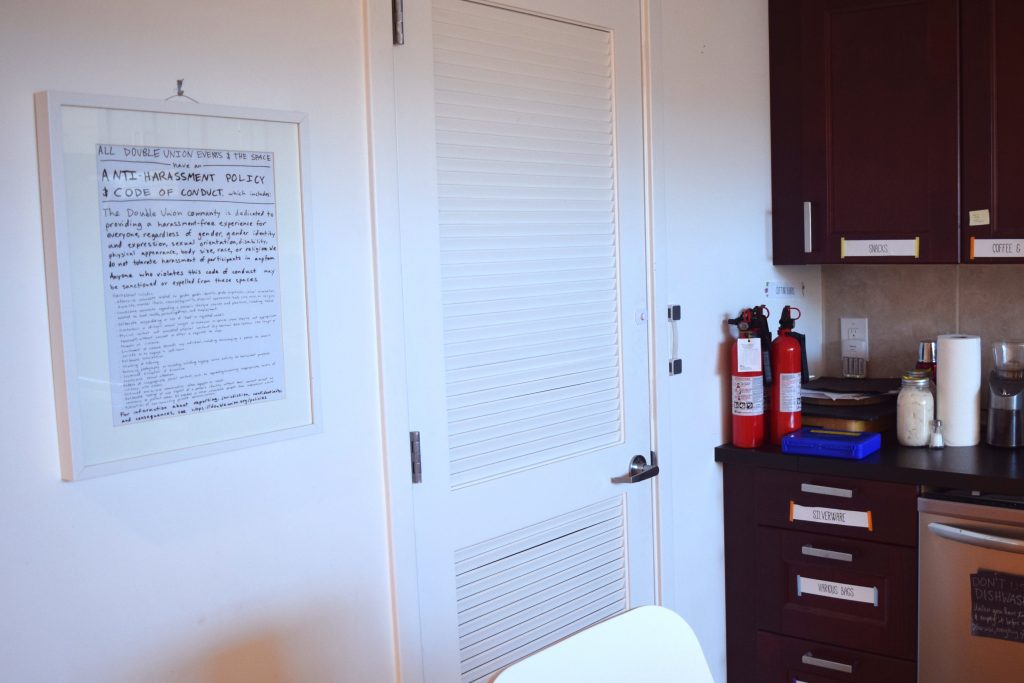

Several feminist makerspaces have popped up around the USA (“Feminist and women’s hackerspaces,” n.d.). These are welcoming spaces for artists, crafters, technologists, and entrepreneurs who may struggle to feel comfortable in mainstream, men-centered spaces due to their gender identity (Fox, Ulgado, & Rosner, 2015; Toupin, 2014). They are typically organized around a strong Code of Conduct that lays out what is expected of their members, and—unlike in most other makerspaces—potential members are vetted before being able to join.

Figure 2. Double Union, a feminist makerspace in San Francisco, CA, have hung a framed copy of their anti-harassment policy and Code of Conduct on their kitchen wall.

Figure 3. Mothership HackerMoms, a feminist makerspace in Berkeley, CA, provide childcare facilities and a playroom so members can bring their young children along.

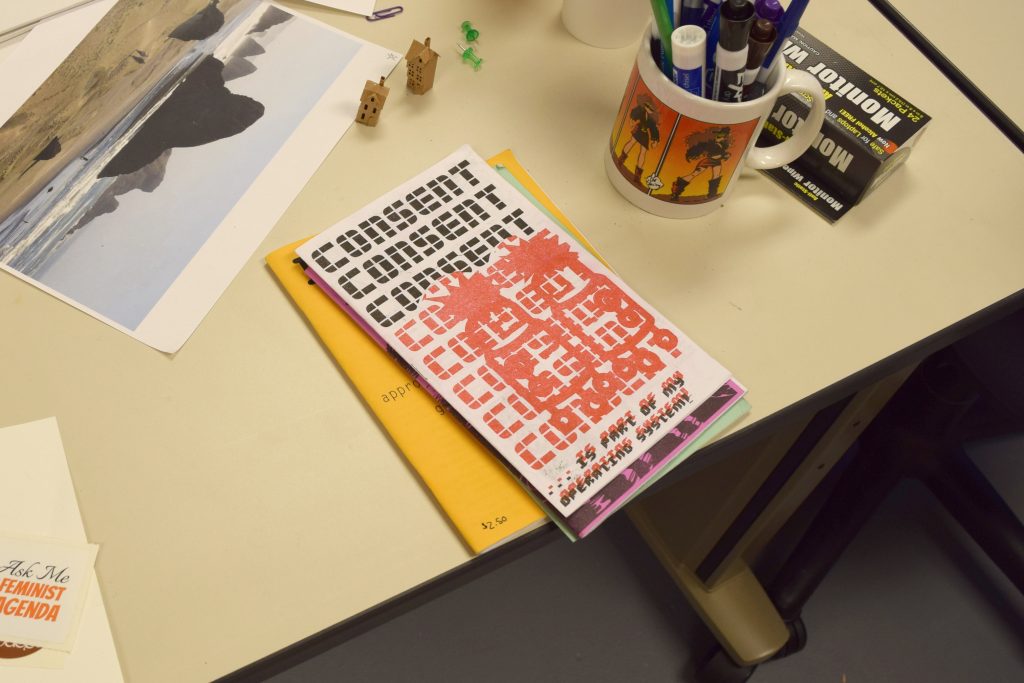

By providing childcare facilities, hosting consent workshops, building feminist and anti-racist book and zine libraries, and providing bursaries for members with low incomes, these spaces signal to woman-identifying and non-binary people that makerspaces are for “people like them”. These feminist spaces give the lie to the claim that the lack of gender diversity in the maker movement is because women just aren’t interested in hacking and making things (Henry, 2014), and this is increasingly being reflected in efforts to provide visible markers of gender inclusivity in mainstream makerspaces.

Figure 4. Consent literature available at Seattle Attic, a feminist makerspace in Seattle, WA.

Figure 5. A mural at Noisebridge, an anarchist hackerspace in San Francisco, CA, depicts the iconic figures Nikola Tesla and Margaret Hamilton. Hamilton coined the term “software engineering” and led the team who developed the flight software for the Apollo space program.

Maker communities have long clustered around areas of economic deprivation, often (ironically) due to the collapse of manufacturing industries that the maker movement has been heralded as reinventing (Anderson, 2012; Dawkins, 2011). The institutionalization of the maker movement and the recent attention paid to it by governments and private companies has led to makerspaces and maker events receiving grant funding and sponsorship as part of schemes to regenerate or upskill local communities (Libraries Taskforce, 2017; The White House, 2015). Often these spaces find that it is not enough to simply provide tools and expect people to use them: they need to make themselves relevant to their community by developing a dialogue with them and finding out how to meet their needs.

Figure 6. The Remakery is based in a multi-ethnic area of south London, England. They were funded via a grant from their local council to provide workspace and tools for reducing waste and tackling social issues in their local area.

Figure 7. Knowle West Media Centre is an arts centre and charity in an area of economic deprivation in Bristol, England. Their makerspace, The Factory, runs free digital design and fabrication workshops for local residents.

As the maker movement matures, communities who were previously focused on figuring out the basic logistics of organizing a makerspace and staying afloat now have more time, money, and energy to devote to including under-represented groups. Makerspaces are working with members with physical disabilities to make their workshops more accessible (Brady, Salas, Nuriddin, Rodgers, & Subramaniam, 2014; Meissner et al., 2017), makerspaces for young people are dedicating resources to engaging youth from low income or minority ethnic families (Calabrese Barton, Tan, & Greenberg, 2017; Vossoughi, Escudé, Kong, & Hooper, 2013), and national networks of Men’s Sheds are supporting the spread of makerspaces for retired men at risk of social isolation (Cordier & Wilson, 2014).

Figure 8. rLab in Reading, England, hosts the Reading Repair Cafe where local residents can get help to repair broken items. They are currently updating their workshop to be more accessible for members and visitors who use wheelchairs.

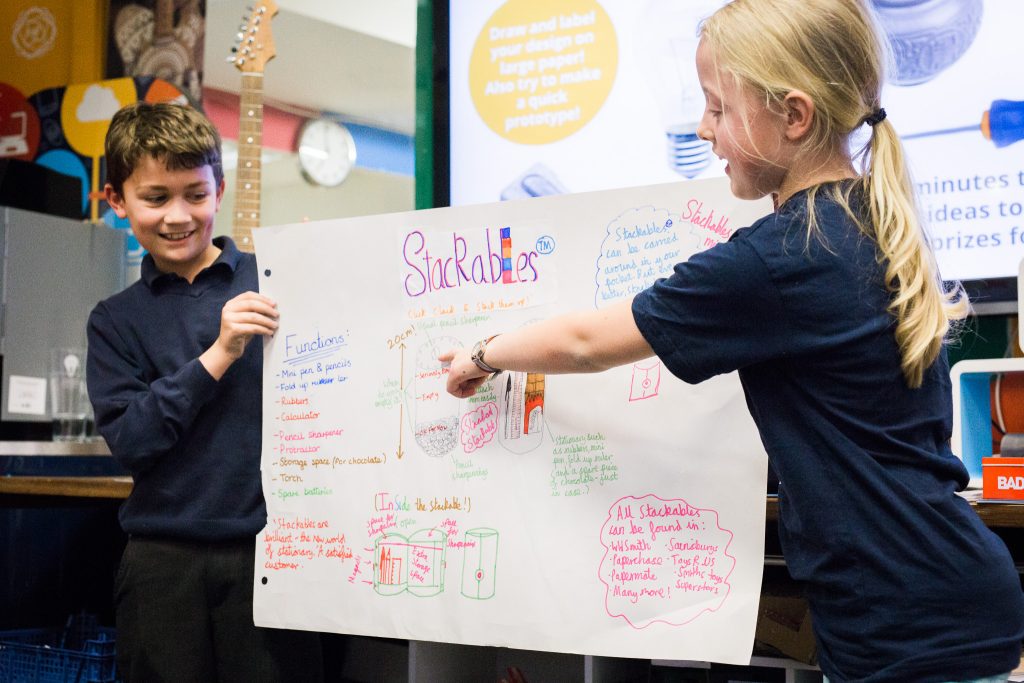

Figure 9. MakerClub is a network of after-school clubs in makerspaces across England. Their Bright Sparks program provides free memberships for children from low income families, sponsored by local digital businesses. (Photo by Chris Quigley, courtesy of MakerClub)

There is still a lot of work to be done, and many challenges to face. Makerspaces struggle to find affordable, accessible properties with adequate parking or good public transport connections. There are ethical issues around receiving grant funding—particularly from military organizations such as DARPA (Altman, 2012; Vossoughi, Hooper, & Escudé, 2016)—and sponsorship agreements typically introduce extra administrative overheads for makerspace organizers. The current political climate in the USA is making things difficult for feminist organizations, and there is a continuing lack of attention to the absence of people of color and the maker movement’s role in gentrification. It is therefore essential to keep these conversations going in our maker communities, and to continue to strive to be excellent to each other.

Reference List

Altman, M. (2012). Hacking at the crossroad: US military funding of hackerspaces. Journal of Peer Production, 2. Retrieved from http://peerproduction.net/issues/issue-2/invited-comments/hacking-at-the-crossroad/

Anderson, C. (2012). Makers: The new industrial revolution. London, England: Random House.

Brady, T., Salas, C., Nuriddin, A., Rodgers, W., & Subramaniam, M. (2014). MakeAbility: Creating accessible makerspace events in a public library. Public Library Quarterly, 33(4), 330–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/01616846.2014.970425

Calabrese Barton, A., Tan, E., & Greenberg, D. (2017). The makerspace movement: Sites of possibilities for equitable opportunities to engage underrepresented youth in STEM. Teachers College Record, 119(6).

Cordier, R., & Wilson, N. J. (2014). Community-based Men’s Sheds: Promoting male health, wellbeing and social inclusion in an international context. Health Promotion International, 29(3), 483–493. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dat033

Dawkins, N. (2011). Do-it-yourself: The precarious work and postfeminist politics of handmaking (in) Detroit. Utopian Studies, 22(2), 261–284. https://doi.org/10.5325/utopianstudies.22.2.0261

Feminist and women’s hackerspaces. (n.d.). Retrieved July 29, 2017, from http://geekfeminism.wikia.com/wiki/Feminist_and_women%27s_hackerspaces

Fox, S., Ulgado, R. R., & Rosner, D. K. (2015). Hacking culture, not devices: Access and recognition in feminist hackerspaces. Presented at the 18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, Vancouver, BC. https://doi.org/10.1145/2675133.2675223

Henry, L. (2014, February 3). The rise of feminist hackerspaces and how to make your own. Retrieved May 30, 2017, from https://modelviewculture.com/pieces/the-rise-of-feminist-hackerspaces-and-how-to-make-your-own

Libraries Taskforce. (2017). Libraries and makerspaces (Guidance). London, England: Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/libraries-and-makerspaces/libraries-and-makerspaces

Meissner, J. L., Vines, J., McLaughlin, J., Nappey, T., Maksimova, J., & Wright, P. (2017). Do-it-yourself empowerment as experienced by novice makers with disabilities. In Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Designing Interactive Systems (pp. 1053–1065). Edinburgh, Scotland. https://doi.org/10.1145/3064663.3064674

The White House. (2015, June 11). Presidential proclamation – National Week of Making, 2015. Retrieved April 24, 2018, from https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2015/06/11/national-week-making-2015

Toupin, S. (2014). Feminist hackerspaces: The synthesis of feminist and hacker cultures. Journal of Peer Production, 5. Retrieved from http://peerproduction.net/issues/issue-5-shared-machine-shops/peer-reviewed-articles/feminist-hackerspaces-the-synthesis-of-feminist-and-hacker-cultures/

Vossoughi, S., Escudé, M., Kong, F., & Hooper, P. (2013). Tinkering, learning & equity in the after-school setting. Presented at FabLearn 2013, Stanford, CA.

Vossoughi, S., Hooper, P. K., & Escudé, M. (2016). Making through the lens of culture and power: Toward transformative visions for educational equity. Harvard Educational Review, 86(2), 206–232. https://doi.org/10.17763/0017-8055.86.2.206

About the author

Em O’Sullivan is a PhD researcher at University College London exploring the intersections between gender and technology in makerspaces. They’re a former makerspace and Maker Faire organizer and are passionate about making maker communities more inclusive. Their research blog is available at freakatoms.co.uk

Em O’Sullivan, Department of Science and Technology Studies, University College London.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Em O’Sullivan, UCL Department of Science and Technology Studies, Gower Street, London, WC1E 6BT. E-mail: em.osullivan.15@ucl.ac.uk