by Martin Charter

Background

Over the last thirty years different perspectives on waste have been seen around the world by the author. Back in the late 1990s in Zimbabwe, a crashed car was scavenged for materials in hours for re-use and in Japan, in the mid 2000s there was a visit to five of 50 electronics recycling factories that had been launched the day the country’s waste electronics legislation came into place. Closer to home, an increasingly number of “end of life” phones, laptops and printers are being stored in my and other people’s lofts and garages. In a recent capacity building project with five re-use social enterprises in Hampshire in the UK, many products were observed that had been designed – deliberately or not – not to be easy to disassemble, and fix or repair. Companies can design products to be easier to be disassembled and repaired to enable extended product life but they are generally not doing so at present.

Between 1995-2016, the author’s team at The Centre for Sustainable Design ® at University for the Creative Arts (UCA) organised twenty-one Sustainable Innovation conferences; this enabled an annual “rain check” on trends and developments in sustainable innovation and design. Over the last few years, an increasing number of examples of grassroots, social, circular innovation have emerged in presentations at the events. These initiatives have been driven by, for example: the increased availability of online videos, information and fora focused on ‘making, modifying and fixing’ products; increased sharing and collaboration of ideas and information; new “places and spaces” being set up to enable citizens to make, modify and fix products; use of new forms of funding e.g. crowdfunding to kick start initiatives; the emergence of new tools (e.g. 3D printing); and growing interest in thinking globally but acting locally.

Repair Cafés have emerged as citizen-driven initiatives to enable the fixing (or repair) of products at a community level. Repair Cafés are part of broader movement of ‘Makers, Modifiers and Fixers’ where individuals and groups of individuals that are ‘making, modifying and fixing’ products are coming together in physical places and spaces that include Hackerspaces, Makerspaces, Fab Labs and Tech Shops.

Fixer Movement

The ‘Fixer Movement’ is being empowered by online platforms, social enterprises and community-based organisations (Charter & Keiller, 2014). This includes:

- Online fixing sites: For example, IFixit ifixit.com an innovative WIKI based website that provides free online repair guides, solutions and ‘how to’ videos for a wide range of consumer electronics and other products, including clothing.

- Social Enterprises: For example, The Restart Project restartproject.org ; a London-based social enterprise that encourages and empowers people to use their electronics longer, by sharing repair and maintenance skills, through Restart events in communities and with companies in the UK.

- Repair Cafés: “Repair Cafés are free ‘community-centred workshops’ for people to bring consumer products in need of repair where they can work together with volunteer fixers, to repair and maintain their broken or faulty products. In addition to repair, many Repair Cafés provide assistance with product modification, particularly to clothing to improve fit and appearance” Charter & Keiller, 2016 (The Repair Cafe WIKI)

Repair Cafes

My personal journey into the world of repair cafes started at the Hannover Fair in Germany in 2014, with an inspiring presentation by Martine Postma, the founder of the then Repair Café International Foundation (RICF). It highlighted that there had been no primary research into the activities of repair cafes and so the author approached Martine to collaborate on a survey to understand what was going on worldwide. An online survey was then completed by The Centre for Sustainable Design ® (CfSD) at University for the Creative Arts (UCA) with RCIF (Charter & Keiller, 2014). Key findings based on 158 respondents included that the motivations for volunteers in engaging with repair cafes were both social and environmental including giving “something back to community” and “feeling involved with others”, alongside helping repair broken stuff. A conference was then organised to disseminate the findings which generated a lot of interest. As a result the author decided to translate the results of the survey into action and opened dialogue with a local Farnham-based NGO – Transition Town Farnham – to collaborate on the development and delivery of Farnham Repair Café (FRC) as a university-community project and “living laboratory” focused on local social and circular economy activities.

The Repair Café Foundation (now Repair Cafe International Foundation (RCIF)), was founded by an ex-journalist Martine Postma in the Netherlands in 2011 to enable people to come together to provide a free service to their community to help repair and therefore, to extend the life of products that would otherwise end up as waste. RCIF has 1,562 Repair Cafés in 35 countries registered on their website (Repair Cafe International, 2018); however, there are indications that there are also a significant number of other Repair Cafés and other community repair workshops that are not on the RCI website.

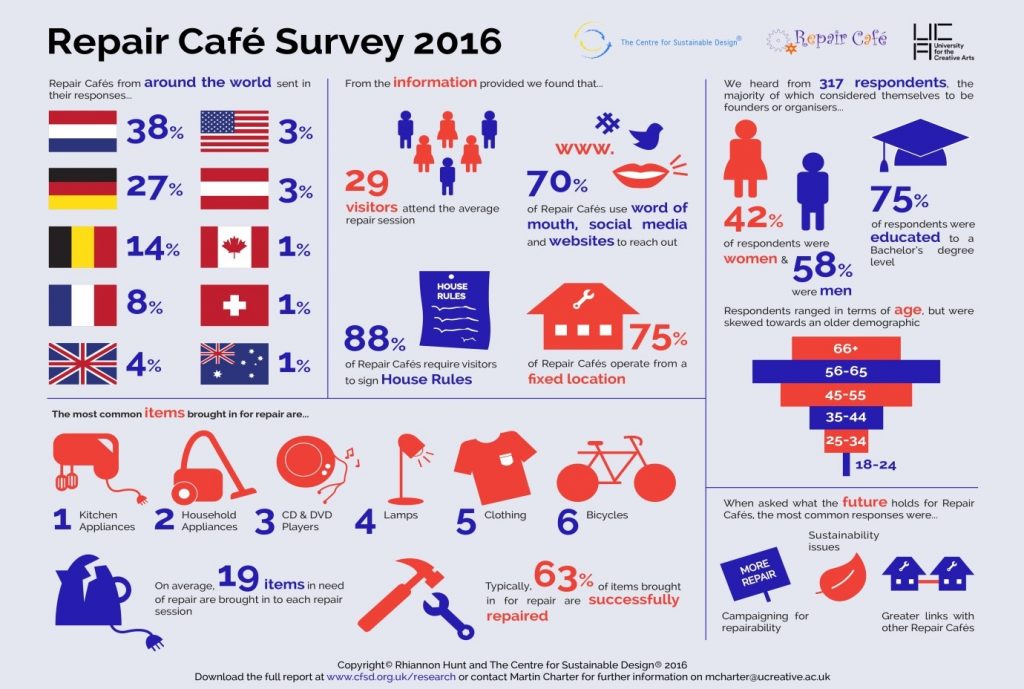

A second worldwide survey of Repair Cafes was completed in 2016 by CfSD at UCA with RCIF (Charter & Keiller, 2016b) produced a range of other interesting findings based on 317 respondents:

- Start-up phase: 72% of Repair Cafés had operated for two years or less compared with 95% in the 2014 survey.

- Citizen-driven: 46% of Repair Cafés were founded by an informal group of motivated individuals and 44% by a single motivated individual.

- High repair rates: 63% of products brought to Repair Cafés sessions were repaired

Figure 1: Global Repair Café Survey, 2016

Farnham Repair Café (FRC): Case Study

After an initial innovation workshop, two pilot sessions were organised to test and learn about the logistics of operating a Repair Café. FRC was launched in February 2015 and in April 2017 became a charity (Farnham Repair Café, 2018a). FRC is based at a fixed venue – United Reformed Church in Farnham – and as at March 2018 has held thirty-six, 2.5 hour sessions. Repair stations are organised for a range of consumer products e.g. electronics, mechanicals, bicycles, clothing, furniture and creative (upcycling). Volunteer repairers bring their own tools and equipment, and a number of repairs are finally completed by volunteers at ‘home workshops’. The FRC management team have developed methodologies to collect data to measure the impact of activities.

Fig 2. Farnham Repair Cafe

Getting involved and taking forward FRC as community repair project has been both rewarding and challenging particularly in moving FRC to be the UK’s first repair café charity.

| Visitors to FRC | 1571 |

| Repairs completed | 553 |

| Repair rate | 63% |

| Landfill diversion | 1.8 tonnes |

| CO2 reduction | 15.0 tonnes |

| Satisfaction | 98%* |

| Citizen savings | £40,827** |

* Exit survey of visitor satisfaction of FRC service

**As result of repairs completed, cost saved from not having to buy a new product

Table 1. Farnham Repair Café: Results to date (April 2018)

Below are a range of reflections and lessons learnt by the author based on three research surveys (Charter & Keiller 2014, Charter & Keiller 2016b,c) and experience from organising thirty-six FRC sessions.

Growing interest

The number of Repair Cafes in the UK has roughly doubled to 58 during 2017-18; and has increased to 1562 worldwide (Repair Cafe International, 2018). FRC has seen growth in interest and attendance since launch.

| Year | Number | Visitors | No. of Products – Booked in | No. of Successful Repairs | % of Successful Repairs | Landfill diversion (kg) | CO2 reduction (kg) | Satisfaction (%) |

| 2015 | 10 | 403 | 159 | 98 | 61% | 369 | 3068 | N/A |

| 2016 | 11 | 395 | 197 | 126 | 63% | 352 | 2929 | 97% |

| 2017 | 10 | 524 | 344 | 218 | 64% | 646 | 5376 | 98% |

| 2018 | 5 | 249 | 185 | 111 | 62% | 438 | 3649 | 99% |

| Total | 36 | 1571 | 885 | 553 | 63% | 1804 | 15022 | 98% |

Table 2. FRC Analysis as at April 2018

FRC actively promotes the impact of its monthly sessions through social media and has been featured on national and local radio, Brazilian television and local press. Awareness of FRC is beyond the local community and it has been consulted by a new repair cafe start-up in Northern Ireland and visited by others from Surrey, Hampshire and Essex; FRC sees supporting the set-up of other repair cafes as part of its wider mission.

Fig 2. Vacuum cleaner repair

Audience

The average age of visitors (product owners) to FRC is 53, with 86% of respondents aged over 45 (Charter & Keiller, 2016c); the on-going challenge is to attract younger people and younger families who perhaps tend to buy new stuff rather than get it repaired. There has been a very positive reaction to FRC – “what a great idea”, “I really don’t like to throw things away” – especially amongst older visitors. FRC has a 98% customer satisfaction rate since monitoring started in June 2016 and has only faced two problematic customer cases that both arose partially as a result of failure in administrative systems that led to changes. Many visitors don’t have the skills to fix products and a number of older visitors have lost the dexterity to sew, for example. Talks at local events and feedback at FRC sessions has reinforced the existence of a segment of more advanced, citizen repairers that are fixing products by using online videos, fora and information with some using FRC for a 2nd opinion when they cannot repair a product. Research amongst FRC visitors has also identified that over 60% of visitors (and volunteers) stated that attending FRC had made them more or much more likely to attempt to repair their own products (Charter & Keiller, 2016c). This finding reinforces the FRC philosophy that is exemplified by the twitter hastag #sharerepair e.g. the desire by FRC that visitors physically observe the repair process and learn.

What visitors say about FRC

“There is a wealth of experience, knowledge and goodwill in the team, and patience in dealing with the variety of issues brought in!”

“How wonderful to have something repaired, and to not need to buy a new hairdryer. Very grateful.”

“What brilliant, supportive people live in our community! How to check to see if hoover belt is broken. Thank you so much.”

“Don’t throw anything away as it may be repaired – quickly too at the Café.”

“How skilful repairers are, how confident, how generous with time and expertise.”

“10/10 for dogged persistence to repair a tricky fault in my iron. Thank you! Keep up the good work.”

Volunteers

FRC experience is that there are amazing repair skills that are just sitting in the community. There are an estimated 72 repairers and other volunteers who have attended at least one session with a core group of around 20-25 who regularly attend sessions. FRC repairers are essentially problem-solvers with many being “owner-completers” who like to solve/complete repairs even if they cannot be completed within 2.5-3 hour sessions. A small number of dedicated repairers will often take jobs back to their home workshops, then attempt fixes and return products to owners direct – fixed or unfixed. Several repairs have gone beyond logical fault diagnosis and fixing, with repairers having developed creative solutions resulting from lateral thinking (Farnham Repair Café, 2018b). Repairers at FRC are happy to bring their own tools as there is a lack of appropriate facilities at the venue which makes storage of tools, parts and components impractical. Replacement parts and/or components that are identified by repairers during the repair process are purchased online by visitors and brought for fixing at the following session.

Local community

Repair is the key mission of Repair Cafes but it has become clear that there is a social role in helping to provide a friendly place that contributes to a sense of community. In addition, there are local economic benefits. FRC has saved Farnham citizens an estimated £40,827 through repairs – meaning that new products do not have to be bought. FRC has worked closely with local stakeholders throughout its development: United Reformed Church provide a hall for FRC and repairers and visitors use URC’s adjacent Spire Café for teas and coffees; Farnham Town Council has been consistently positive about FRC and, for example, allowed FRC to temporarily piggy-back on its insurance policy whilst it was in transition towards a charity; University for the Creative (UCA) provided legal advice via its solicitors in relation to the charity submission and donated a PAT tester. The connection between CfSD at UCA has been integral to development and has provided administrative support, statistical analysis and ad hoc research. Reports have been uploaded to www.cfsd.org.uk/research to provide wider access, presentations have been given, articles written and two chapters have been completed on Repair Cafes and FRC for an upcoming book (Charter, 2018).

Figure 3. Strengths of Farnham Repair Café, Charter & Keiller, 2016c

Products

There are a wide range of products that have been booked in and fixed over 36 sessions, from a reel-to-reel tape machine to a Japanese doll to toys and vacuum cleaners. Electronics is always the most busy work station, and is a “hive of activity” with the highest proportion of repairers. Unpublished research by a FRC trustee based on 261 repairs between 14th February 2015 to 9th July 2016 provided some interesting data.

- Clothing is the most common product needing repair

- 4 failure types account for nearly 50% of all repairs

- It costs less than £1 in new parts to successfully repair over 70% of products

The top five products needing repair were: clothing (12%); lighting (7%); portable radio/CD players; sewing machines; and bicycles. The top five product failures were: worn or torn (14%); poor maintenance/adjustment (12%); broken/cracked parts (11%); electronic parts at component level (11%); and internal or external wiring failures – excluding power cords (7%).

Fig 3. Clothing repair

At the time of the analysis, FRC had an impressive repair rate of 82% leaving FRC successfully or partially repaired:

- 63% Successfully completed repairs of

- 19% Partially completed repairs

- 5% Not completed but advice given

- 12% Unsuccessful

Over 36 sessions, the FRC repair rate is 63%, which is in line with the global average of 63% (Charter & Keiller, 2016b). FRC repair rate is still intuitively very high given that there is only 2.5 – 3 hours to repair products per session, and a small group that complete repairs at home workshops.

Fig 4. Toaster Diagnosis

Organisation

Although FRC is a charity, it is run in a business-like manner, with all trustees having been senior managers or directors of companies. There has been strong commitment and motivation by all key stakeholders related FRC particularly the trustees and repairers. A full set of promotional tools have been used to attract repairers and visitors (product owners) to FRC including local press, local radio, e-marketing, Facebook, Twitter, leaflets, presentations to local groups, local social networks and a webpage http://cfsd.org.uk/events/farnham_repair_cafe/. Minimisation of risk is a key issue for FRC and it has a health and safety policy, and public liability and products liability insurance in place. Research completed by FRC indicated that few insurance companies or brokers understood Repair Cafes and the actual risks associated with products fixed at Repair Cafés; with the biggest concerns being electrical and electronics products. FRC’s venue is the United Reformed Church (URC) which is a central location in the town; other venues were considered but were rejected as URC is an excellent location with nearby car parking facilities.

Development

FRC was originally set up as a collaborative project (without legal status) by CfSD at UCA and Transition Town Farnham (TTF). Several early UK based Repair Cafes had been set up as projects within Transition Towns (Transition Towns, 2018). The difference compared to other similar situations in the UK was that FRC was set-up as collaboration between CfSD at UCA and TTF, and not set-up directly by TTF and therefore TTF did not, metaphorically, own it. The arrangement was useful in the start-up phase of FRC as TTF provided access to its bank account to deposit donations and small grants, and make payments, and the relationship also enabled FRC to be incorporated into TTF’s existing insurance policy. However, the relationship became more challenging over time due to differing perspectives from the individuals involved, differences in vision, gaps in practical experience between the collaborators, and differing commitments. A key lesson learnt is to always thoroughly understand who you are “getting to bed with” before you formalise collaborations to ensure that all key stakeholders involved in the development and organisation of a Repair Café have the same vision, motivations and expectations.

In Q4 2016, it was decided by the FRC core team that it should apply to register as a charity to gain legal status. The application process was quite challenging, as was untangling activities from TTF. The registration was submitted in January 2017 and after various rounds of comments with the Charity Commission, charity status was granted on 18th April 2017. FRC has also helped spawn other initiatives and research. As a result of connections made through a separate repair project in Hampshire that CfSD had partnered in, one of the FRC trustees now leads a Men’s Shed (Men’s Sheds, 2018) at the Furniture Helpline (Furniture Helpline, 2018) in Bordon. Another trustee is completing a postgraduate degree in sustainable development at the University of Surrey with his thesis focused on CO2 impacts of repair cafes in the UK. Also additional research amongst FRC visitors was completed by the Open University that was presented as a research paper at a conference (Dewberry et al, 2016). FRC is presently considering the development of additional added-value services for the local community, and increased dissemination its experience and understanding.

Fig 5. A tape recorder is fixed

Ten lessons for Repair Café start-ups

- Establish a clear vision: short, medium and long-term

- Ensure there is a person who is prepared to lead, coordinate and plan activities

- Recruit a steering board drawn from repairers and other local citizens with business experience

- Establish clear financial and marketing plans

- Identify a central location with good access for visitors (product owners) and repairers

- Ensure you have a legal structure for insurance and banking purposes

- Use a range of communication tools to attract repairers and visitors

- Develop a positive and friendly community-oriented atmosphere

- Monitor the environmental, social and economic impact of repair activities

- Develop good relationships with key local stakeholders (local council, university, etc.)

Endnote

Experience from Repair Cafes is illustrating that a significant number of products are not designed for disassembly and reparability. There is growing discussion over whether this is as a result of built-in product obsolescence arising from bad design and/or deliberate strategies. Transitioning towards the Circular Economy (CE) at a ‘product level’ or product circularly will mean that there will need to be increased focus on the use or re-use stage of the lifecycle rather end-of-life. It will be about proactively building into the design and development phase of products-services, strategies to enable maintenance, repair, refurbishment, reconditioning, upgrading, remanufacturing, parts harvesting and finally recycling. In CE terms, recycling should be thought of, as much further down the line, than in traditional lifecycle thinking. Implementing product circularity should lead to an extended lifecycle perspective where products, components and materials are kept in the system to the highest value over the longest time period. However, a key issue is not to lose the lifecycle perspective and to become myopic e.g. trade-offs with other environmental aspects need to be considered. CE does not operate in a vacuum, and is not a panacea (Charter, 2018).

Note

Martin Charter also created a poem based on his repair café experiences, which was performed at the Tate Modern in October 2017, and is available in two online formats (Charter 2017a, Charter 2017b, Charter 2017c).

References

Charter M, 2018. Designing for the Circular Economy. Routledge. London: UK

Charter M. , 12th-15th October 2017a. Sounds of a repair cafe. [Public performance of poem at exhibition] London: Space Gather Make @ Art: Work: Tate Modern Online: http://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/tate-exchange/workshop/artwork [Accessed: 10th May 2018]

Charter M, 2017b. Sounds of a repair cafe. [Audio piece: shared machine sound] London Online: https://spacegathermake.tumblr.com/audio [Accessed: 10th May 2018]

Charter M., 2017c. Sounds of a repair cafe. [Poem]. Farnham: Farnham Repair Cafe Online:https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCkzO-v8mM-TeEf_dFqV5pCw [Accessed: 10th May 2018]

Charter, M. and Keiller, S, 2014. Grassroots Innovation and the Circular Economy: A Global Survey of Repair Cafés and Hackerspaces. Online: http://cfsd.org.uk/site-pdfs/circular-economy-and-grassroots-innovation/Survey-of-Repair-Cafes-and-Hackerspaces.pdf [Accessed: 4th March 2018]

Charter, M. & Keiller, S, 2016a. The Repair Café WIKI. Online: http://repaircafe.shoutwiki.com/wiki/Main_Page [Accessed: 4th March 2018]

Charter, M. & Keiller, S., 2016b. The Second Global Survey of Repair Cafés: A Summary of Findings Online: http://cfsd.org.uk/site-pdfs/The%20Second%20Global%20Survey%20of%20Repair%20Cafes%20-%20A%20Summary%20of%20Findings.pdf [Accessed: 4th March 2018]

Charter, M & Keiller, S, 2016c. Farnham Repair Café: Survey of Visitors & Volunteers. Online: http://cfsd.org.uk/site-pdfs/Farnham%20Repair%20Cafe%20Survey%202016.pdf [Accessed: 5th March 2018]

Dewberry E, et al. 2016. A Landscape of Repair. Sustainable Innovation 2016. Epsom: UK

Farnham Repair Café, 2018a. Online: http://cfsd.org.uk/events/farnham_repair_cafe/ [Accessed: 4th March 2018]

Farnham Repair Café, 2018b. Farnham Repair Café: Case Studies. Online: http://cfsd.org.uk/events/farnham_repair_cafe/ [Accessed: 4th March 2018]

Furniture Helpline, 2018. Online: https://www.furniturehelpline.co.uk/about/what-we-do/ [Accessed: 6th March 2018]

Men’s Sheds, 2018. Online: https://menssheds.org.uk/ [Accessed: 6th March 2018]

Repair Café Foundation, 2015. Joint Mission statement. Online: http://repaircafe.org/wpcontent/uploads/2015/03/Mission_Statement_Reparability_and_Durability_of_Products.pdf [Accessed: 4th March 2018]

Repair Cafe International, 2018. Online: https://repaircafe.org/en/visit/ [Accessed: 10th May 2018]

Transition Towns, 2018. Online: https://transitionnetwork.org/ [Accessed: 10th May 2018]

about the author

Professor Martin Charter MBA FRSA has worked as a manager, researcher and trainer on sustainable innovation and product sustainability for 30 years in academia, business and consultancy. He is the founding Director of The Centre for Sustainable Design ® at University for the Creative Arts (UCA) and Senior Associate, Business School for the Creative Industries at University for the Creative Arts (UCA). He is the author/co-author of Greener Marketing 1 & 2, Sustainable Solutions, System Innovation for Sustainability, Eco-innovate and Designing for the Circular Economy (July 2018). Martin is the Chairman, Board of Trustees, Farnham Repair Café, and a regular speaker in conferences worldwide.