Keywords:

Hack Labs, One Laptop Per Child, OLPC, ICT for Education

Anita Say Chan

Introduction

Standing atop a high stage at the Interactive Technology Camp in Lima, public school teacher Eleazar Mamani Pacho flips through several slides featuring the rural elementary school where he works as principal and teacher. The images introduce the Aymara students and indigenous community in the Andean village of Lacachi where he teaches among to his audience, a mixed crowd of elite international policy makers, global education experts, and urban corporate representatives of IT firms sponsoring the education-oriented event – from Microsoft, to Intel and Telefónica. Organized in 2012 by Peru’s Ministry of Education in collaboration with the World Bank and US Embassy at the University of Lima, the two-day event drew over 1000 participants to Peru’s capital city to hear presentations on the latest innovations in educational technologies from a range of stakeholders, institutional actors, and individuals – including educators like Pacho, the only speaker to represent rural schools at the event. A few the images he lingers on showcase his students in the regional dress and dance performed during traditional festivities in Puno, others feature them in groups over the dry flat fields of Puno’s Altiplano. And others feature students working on class activities developed by Pacho which had earned him the invitation to travel from Puno to participate in the global event – those developed as classwork and digital pedagogy for the XO Laptop, the centerpiece of the MIT-launched global One Laptop Per Child initiative.

The visibility Pacho’s efforts in Puno around local educational technologies and XO use was indeed unexpected. Better known within the national imaginary for its large indigenous Aymara and Quechua populations, cold stretches of Andean altiplano, and quinoa, potato, and alpaca wool production, Puno has typically been summoned among Lima’s governing elite as the remote other to the capital city’s modern cosmopolitanism (Jacobsen 1993). [1] Nonetheless, it was from there that the first XO-based users manual – a 100-page, teacher-centered text distributed online and translated from Spanish into English, French, and Arabic – was published (Salas 2009). It was there too, that alongside efforts to organize some of the largest conferences for rural teachers’ XO use, that workshops for translating XO software into Quechua and Aymara began, organized with indigenous language activists and elders, aiming to be among the XO’s first indigenous language localizations. It was there that schools like Lacachi gained a reputation for being among the more successful regional XO cases, where students maintained routine use of laptops. And it was there that Pacho, with several local teachers and engineers, had notably united to form one of Peru’s first rural hack lab collective, Escuelab Puno.

Pacho, however, stressed none of those achievements in speaking to his international audience. He used the floor instead to underscore the deep techno-fundamentalism that shrouded the arrival of the region’s share of XOs – and recounted how laptops appeared without prior input from teachers, parents, or community leaders. As he described it: “When they arrived, there was no other option [other than to accept them]… But when [the state] gave you the computer, it was really another duty on top of all the [routine] functions that teachers already have, and we were never trained to teach with such tools before.” [2] He stressed that despite the attention his own school had managed to gain around its use of the XO laptops, local teachers’ and rural communities’ concerns, participation, and even innovations around the OLPC program had largely been ignored. As he put it in speaking to me in an interview, “I know there are many teachers who work with the XOs well, people with very successful experiences in their classes. They should be brought together [and organized]… [Because] we’re carrying enormous inequalities in education” and “Without rural and intercultural priorities [around technology], we’ll keep amplifying unequal divides.”

This paper looks too into the foundations and dynamics surrounding the Escuelab Puno’s collaborations – perhaps one of the most surprising spaces from which hack lab collectives, new experiments in techno-cultural collaborations, and critical perspectives on existing techno-fundamentalist orientations, would emerge. As Peru’s southern most province, Puno is known both nationally and internationally as the nation’s folklore capital. Yet it was from there that new, historically-informed critiques started to emerge around the hyper-accelerated investments of the state in its expansive ICT for Education (ICT4E) initiatives, and the contradictions in state framings of “local inclusion” as a core objective of its digital education programs. Years before other critical studies on the OLPC project in Peru (including those by entities like the International Development Bank) were released, rural hack lab networks like Escuelab Puno – that brought together free/libre and open source software (FLOSS) advocates with public school teachers in multi-disciplinary, intercultural collaborations around digital technological uses in classrooms – had started to diagnose and respond to “techno-fundamentalist” underpinnings in ICT4E deployments.

Since 2003, I had followed the development of such networks around free software in Peru, following their extension into rural zones like Puno, where I would encounter an array of unlikely participants – from rural teachers to indigenous language activists – who would be drawn into FLOSS advocacy and reform work based on educational deployments of open technologies in educational institutions (Chan 2004a; 2004b; 2014 forthcoming). By 2009, rural teachers in Puno working around regional OLPC deployments had started to collaborate with local engineers in organizing educational workshops on FLOSS use and conferences oriented around discussing regional technological deployments. Offering alternatives to the state’s official framings of technology as automatic catalysts for education reform across the nation, their efforts would culminate by 2011 in conferences around that drew in some 400 participants — including rural, indigenous teachers from across Puno’s villages and transnational open media and language activists from Lima, Ecuador, Bolivia, Argentina, Spain, and Finland.

This paper, based primarily on ethnographic fieldwork and interviews conducted between 2010-2012 with some three dozen local and global collaborators in Peruvian hack labs in Lima and Puno, aims to explore how and why such collectives were able to develop such a critical counter-balance to the techno-fundamentalist ethos that frequently unpins ICT4E initiatives. Their critiques would make visible how models of techno-fundamentalism powerfully operate in local ICT4E deployments, including those around OLPC, which experienced rapid and continual national expansions from 2007-2012, despite the stark lack of evidence supporting pedagogical efficacy. Within that period, OLPC in Peru grew from a pilot program of less than 2000 laptops in 2007 to a nationally-scaled project distributing over 900,000 XOs by late 2011. This paper explores the means by which such hefty expansions and investments are fueled by “techno-fundamentalist” framings, and rely upon such framings’ ability to gain traction beyond engineering and design circles. And it explores too the means by which local hack lab networks, as a crucial response to such developments, have cultivated their own multi-disciplinary global collaborations to extend critical alternatives of such framings. Beyond developing spaces for shared access to new technologies, the cultural work of building cross-disciplinary networks has been key to the role local hack labs in Peru have served, in the context of national ICT4E expansions. The dynamics and social structures that can either enable or truncate the flow of techno-fundamentalist framings, this work suggests, invites closer study, given how powerfully such framings – beyond Peru – have gained purchase and been rapidly transformed into national policy before debate among key sectors of the public and stakeholder populations can take place.

Global Encounters: Prospective Futures and Techno-Fundamentalist Interfaces

Just months following the Interactive Technology Camp in mid-2012, the first large-scale study OLPC was released by the Inter-American Development Bank. Widely anticipated by education, technology, and policy experts worldwide, the study focused on pedagogical impacts in Peru – OLPC’s largest partner nation, where nearly 1 million XO laptops were deployed in public schools as national policy – but had implications for similar initiatives that deployed another 2 million OLPC laptops in 42 other nations. And much like the more recently emerging studies on Massively Open Online Courses (MOOCs) growing across US campuses, [3] the report raised significant questions on the results of the large and rapidly expanded institutional investments in un- or under-tested digital technologies. It stated, “OLPC aims to improve learning in the poorest regions of the world… The investments entailed are significant given that each laptop costs around $200, compared with $48 spent yearly per primary student in low-income countries and $555 in middle-income countries. [Yet], there is little solid evidence regarding [its] effectiveness.” It continued: “Although many countries are aggressively implementing the OLPC program … [n]o evidence is found of effects on enrollment and test scores” (Cristia et al. 2012).

Such sober findings notwithstanding, it’s become increasingly clear that investing in new ICTs and the discursive framings of elite global engineers and digital entrepreneurs continue to fundamentally impact national policies, particularly in relation to education. Educational technology analysts note the continuing expansion of ICT4E initiatives worldwide that claim to prepare diverse learner populations for a competitive, 21st Century information-centered economy through extending new digital technologies (Bajak 2012; Cristia 2012; Cristia et al. 2012; Oppenheimer 2012; Severin and Capota 2011; Trucano 2012). A range of nations – 17 documented in Latin America alone as of 2011, and 20 others in African, Asian and Eastern European countries – had launched large scale ICT4E programs that generally claim to extend digital “inclusion,” connect the nation, and enhance future productivity by drawing presumably “disconnected” learning sectors – particularly at risk, minority, indigenous, and economically marginalized populations – into global circuits of exchange (Oppenheimer 2012; Severin and Capota 2011). Tech industry analysts too note how new developments in low-cost, student-centered computing products were spurred, with IT firms like Intel adding some 7 million of its own student-tailored Classmate PC to schools across the Americas (Cristia 2012; Severin & Capota 2011). As IDB policy analyst Julián Cristia wrote, it was evident that OLPC was “just the tip of the iceberg” (2012) in the global spread of ICTs as 21st century “learning solutions.”

Indeed, there’s little doubt that growing investments in new digital education projects continue – in rates that defy critical findings from recent studies, and despite scholarly arguments for more balanced approaches. Moreover, the uptake of such programs can exceed existing infrastructures for producing research. Indeed, their enthused, often un-cautious adoption seems to operate on the accelerated timescales of commercial IT developers than on the deliberative pace of academic researchers. They often betray an uncritical buy-in into the technological framings of the elite engineers and IT designers. Often based in “centers” of IT innovation, such actors’ unshaking faith in the irrefutably transformative power of ICTs express what technology studies scholars have cautioned as a “techno-fundamentalism” (de la Pena 2006; Vaidhyanathan 2006; 2011). Such orientations are related to what have been critiqued before as a technological deterministic framing adopted in historical frameworks, in “which historians often assign determinative power” to technologies as a means of explaining historical change, and thereby “give credence to the idea of ‘technology’ as an independent entity, a virtually autonomous agent of change.” (Smith 1994, xi). In its popular uptake beyond scholarly circles, historian of technology Merritt Roe Smith observes technological determinism surfaces as a largely explanatory force: “It is typified by sentences in which ‘technology,’ or a surrogate like the machine,’ is made the subject of an active predicate: ‘The automobile created suburbia.’… ‘The robots put the riveters out of work.” (Smith 1994, xi).

But whereas technological determinism operates as largely as an explanatory device towards the explanation of the creation of a present condition or presumably self-evident state of affairs, techno-fundamentalism operates more as a predictive device. Originating within elite technological design circles (such as those of the Google engineers), it asserts a “blind faith” in technology’s impacts (Vaidhyanathan 2011, 50) and a “religious” like fervor that maintains and insists upon technology’s solution-making impacts even without evidence to support such beliefs, or worse, in the face of direct evidence to the contrary. In its expression, that is, techno-fundamentalism projects a future vision of change in which a new technology is predicted as operating with the capacity to invariably – and almost “magically” – resolve existing problems. And while such magical transformations may not yet have occurred, and may even seem unlikely to occur given the intractability of the existing problem at hand, change and progress is held out as the promise the new technology is sure to bring. As Siva Vaidhyanathan writes, such faith can indeed operate to “dangerous” ends (verging indeed on historical denialism) when allowed to “affect our expectations and information about the world” (Vaidhyanathan 2011, 81) to such a degree that flurried investments in new technologies that are out of step with reality are facilitated. Or, so too when they prevent more balanced deliberations from taking place.

Crucially, the global circulation of faith-infused framings around the XOs was aided by other actors beyond partnering governments. From the project’s beginning, Nicolas Negroponte, chairman of the OLPC Foundation, and founder of MIT’s Media Lab leveraged supra-national, global governance networks to make his pointedly missionary zeal for the project readily known. At the XOs debut at the World Information Society Summit in Tunis in 2005, he boldly predicted that some 100 to 150 million XOs would be distributed across the world by 2008. Kofi Annan likewise hailed the machine as both “inspiring” and “an expression of global solidarity” (Twist 2005) – praise that won instant international headlines after Annan demonstrated the XOs self-powering by a wind-up crank before a rapt audience of international policy makers.

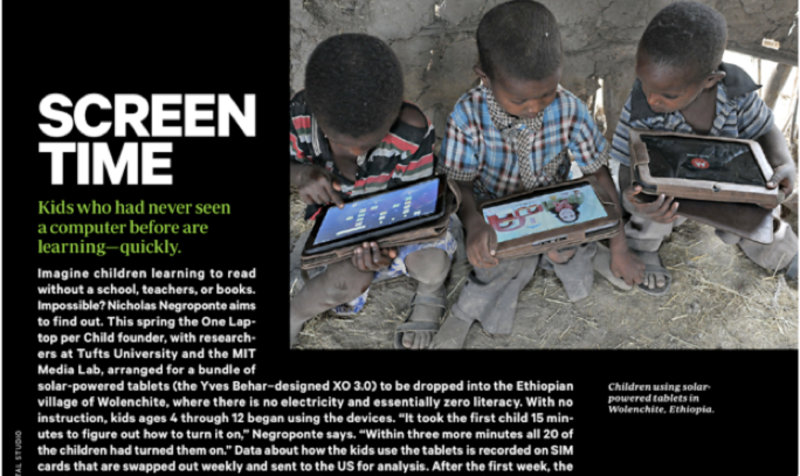

Academic studies began to emerge around the initiative critiquing Negroponte for his unflinching “techno-determinism” (Toyama 2010 2011; Warschauer & Ames 2010), and a chronic resistance to learning from the lessons of local implementations. Such criticisms nonetheless had only modest impacts in slowing the persistent growth of ICT4E initiatives like OLPC (Oppenheimer 2012; Severin and Capota 2011). And Negroponte himself would continue to insist publically that: “Access to a connected laptop or tablet is the fastest way to enable universal learning.” (Negroponte 2010) A long-time adherent to Seymor Papert’s constuctionist learning model that viewed children as radically individualistic, self-directed learners and innate self-teachers, Negroponte further dismissed the need for project evaluation, stating in a September 2009 forum of the International Development Bank, as calls for studies on OLPC’s impacts were starting to emerge: “That somebody in the room would say the impact [of the XO] is unclear is to me amazing – unbelievably amazing… There’s only one question on the table and that’s how to afford it… There is no other question” (Negroponte 2009; Warschauer & Ames 2010). The efficacy of such argumentation in influencing the education policy makers in Peru was demonstrated in the growing expansion of the program – from 400,000 XOs in 2009 to more than double that by the end of 2012 – even after pointed critiques around the program began to emerge from IDB studies. Witnessing the continued global expansions of OLPC, in remarkable defiance of the voices of varied critics and educators, the Peruvian media scholar Eduardo Villanueva wrote incredulously: “OLPC still believes in the power of one technological solution transforming realities as varied as Afghanistan or Uruguay.” (Villanueva 2011)

OLPC leadership insistences that laptop access was “the only” relevant question for remote sites pointedly suggested that existing education-centered actors – from local teachers to local communities – were virtually negligible and could be regarded as external to deployments. [4] That such actors were even suggested to be impediments to “real” learning, was reflected in OLPC’s five “core principles,” which specified in detail the conditions in which laptops should be adopted – indicating that i) children be laptop owners, ii) beneficiaries be aged 6 to 12, iii) every child and teacher receives a laptop, iv) connectivity through a local network or the Internet, and v) software be open source and free. Other local actors’ roles in project deployment, however, remained conspicuously un-addressed – a point that local teachers critiqued in OLPC’s early years in Peru’s rural zones (Chan 2011 2014). Their concerns were echoed by the IDB’s reports that similarly cited the stark imbalance between OLPC’s abundant information supply on student XO adoption and the neglect of other “essential” education factors: “[OLPC’s] underlying vision is that students will improve their education by using the laptop and through collaboration with their peers. However, the OLPC portal provides limited information about how to integrate the computers provided into regular pedagogical practices, the role of the teachers and other components essential for the successful implementation of the model.” (Cristia et. al. 2012, 6)

Yet despite the insistence by OLPC leadership on laptop access as “the only” relevant question for improving education outcomes – and the message’s reverberations through international forums like WSIS and partner governments like Peru’s – attempts to construct more balanced, multi-disciplinary partnerships around new technology deployments were emerging from rural hack lab sites. Ongoing collaborations among local teachers and engineers based in Puno had begun to formalize into the creation of Escuelab Puno – a non-profit, civic association and hack lab focused on developing pedagogical and engineering support for educational technologies’ classroom use. For three years prior to Escuelab Puno’s founding, Puno had been the site of annual workshops organized by local teachers, engineers, FLOSS advocates, and indigenous language activists to discuss XO integration into local schools. Such activity resulted in gatherings that drew more than 400 teachers from across the villages and towns of Puno in the 2011 workshop; and culminated in the launching of Escuelab Puno by a mixed team of five local teachers and FLOSS advocates (Chan 2011; 2014).

Neyder Achahuanco, the young systems engineer and part-time teacher helped co-found Escuelab Puno with fellow Puneneans he’d gradually come to meet throughout his experiments with FLOSS technologies as a teenager. Speaking with me during an interview, he explained how his investments in FLOSS began when he was still in high school and volunteered to help local teachers migrate schools and universities from Windows to FLOSS platforms. Although only 26-year-old now, his first hand observations on Peru’s “digital education” initiatives – and the growing interactions they’ve entailed between education and elite global engineers – already span a decade’s worth of various local, national, and now (with OLPC) globally scaled cases. [5] With some 30,000 XOs deployed in Puno, he made little attempt to veil the critique he’s formed after witnessing various models that privileged engineering expertise and marginalized teachers’ input unfold over the years. As he stated flatly in an interview: “Having an engineer in front of someone [for training workhops], at the front of a room with a group of teachers just listening just does not work. It doesn’t work because engineers weren’t interested in understanding teachers, and teachers are not interested in becoming engineers.”

He made clear too that part of Escuelab Puno’s mission is to caution against the risks of “techno-fundamentalist” orientations that reify the “self-evident” need for rural transformation without envisioning parallel reform potentials in other sites, and that amplify the discrete solution-making capacities of IT and urban technology experts. He specified that among the factors that distinguish Escuelab Puno’s deployment approach is its recognition that such techno-fundamentalist urges and their dependence on narratives of new technologies as forms of “imported magic” (Medina, da Costa Marquez, & Holmes forthcoming) are part of the problem, rather than the solution: “We’ve become very critical of this idea embraced by many technology projects that the only thing that will save education, [or] improve society, is to throw technology at it. To say, ‘Here, take this technology, your magic wand to escape from poverty! Here are your green laptops, your magic wand to improve students… [We forget] there’s a huge, complex, diverse, and highly multi-disciplinary process in what we call education.”

He explained that part of Escuelab Puno’s philosophy is reflected in its aims to foster spaces of dialogue between engineering and pedagogical experts by balancing such representation in its leadership. And he explained that one of the primary objectives that inspired its founding was to facilitate multi-disciplinary collaborations around XO deployments – specifically through a “Partnership Program” the collective proposed to regional and national ministry officials – that would create one-to-one teacher-engineer partnerships in classrooms to collaboratively design local XO instruction techniques and materials. The idea, he specified, was one that emerged only through the involvement of non-engineers in Escuelab Puno’s projects: “The idea of the `Partnership Project´ didn’t suddenly just dawn on us overnight. It was the outcome of almost a year of collaboration with educators, sociologists, Aymara and Quechua representatives – discussions around multiple interests, daily work, and work in rural sites.”

He insisted, moreover, that the partnership model they’ve promoted would operate as much to the benefit of engineers, and their means of deriving solutions through technologies, as much as to local teachers: “Our goal, we realized, was to improve a social problem [rather than a technological one]. Under the direction of just engineers, [we would never] have seen that the problem could be engineers. [Since] engineers always think of themselves as bringing solutions . . . [But] through having multi-disciplinary input . . . we realized that the problem was with us, in how we thought, and in what we said was the miracle solution and magic wand that would resolve everything. We realized we were creating more problems than solutions for teachers.” Pausing for a moment, he underscores how the process of technological translation might in fact operate as much towards the de-centering and reform of technologist’ consciousness, as it works towards the localization of technological artifacts, adding: “But we only achieved this after we sat around the table with everyone together. Only then could we really see what we were all doing . . . as engineers, teachers, sociologists, linguists, or ordinary people.”

National Encounters: Intercultural Resources and Interfacing with the Present

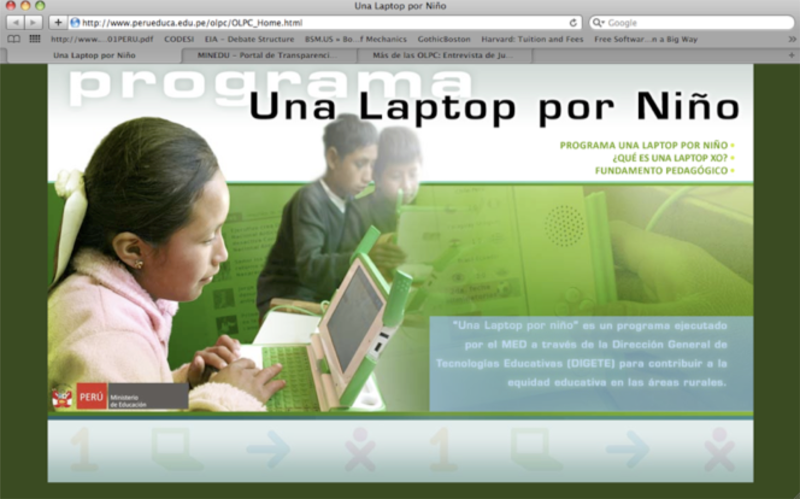

A visit to the Ministry of Education’s website for the OLPC initiative, which pushed forth one of the earliest national framings of computing at the periphery staged another expression of technological fundamentalism for online audiences. After entering the site via a page that features a single profile of a young student with her gaze fixed on her XO laptop, visitors can follow “Testimonials” links to further accounts of rural students with their newly minted XOs. A photo of two girls seated on a grassy slope working with theirs appears beside the quote “Today we dream of a future, tomorrow, we’ll achieve it.” Another image is paired with the statement, “Today I discover, tomorrow I’ll innovate.” And a final image in the column, where seven smiling students raise laptops triumphantly over their heads, is accompanied by the statement: “Today we have our OLPCs, tomorrow we’ll be prepared for the future.” The page of anonymous quotations supplies no further information on where the photos were taken or when quotations were recorded – no names, no dates, no local details – a curiosity, given the $82 million spent for Peru’s nearly 1 million XO laptops (Talbot 2008). The Ministry had even created a new office, DIGETE – the General Direction of Educational Technologies (Direction General de Tecnologia Eduactiva) – shortly after its partnership with OLPC began in 2008 to manage such expansive resources.

Such state-produced visualizations are reminders that the techno-fundamentalist ethos of projects like OLPC aren’t sustained by foreign Western engineers alone, but have relied centrally upon the fostering of local contacts and stewards – whether governments, local universities, or national NGO – to maintain and expand deployments. Oscar Becerra, the former Chief Educational Technology Officer for Peru’s Ministry of Education and the original head of its OLPC deployment, for instance, stressed the capacity of new educational technologies to “integrate” remote citizens in speaking to Western reporters in 2008, in the months before Peru’s pilot program would expand to one of national-scale deployment. Explaining the rapid growth of the program – where some 400,000 XOs were planned for 9000 schools by the year’s end – he stressed how it would allow rural children the freedom to not just imagine their own “future” – but to choose one for themselves. He said: “Our hope for [that student] is that he will have hope. We are giving them the chance to look for a different future… These children who didn’t have any expectation about life, other than to become farmers, now can think about being engineers, designing computers, being teachers – as any other child should, worldwide.” (Talbott 2008) Becerra’s missive underscored a crucial point about the project: that its emphasis on the promise of digitality has as much to do with a stress on the singular power of IT, as it does with extending to “disconnected actors” the option of both global and national inclusion. Through digitality, adopters would be able to enter the same universal operations marked as essential to all contemporary agents – that of thinking, learning, and creating with information – but which are rendered further away, presumably, without hi-tech.

While Lima’s governing elite enthusiastically adopted such a framing of technological pedagogy and digital literacy, a consideration of historical framings of the development of national educational models in Peru, and the extension of new literacies and technologies to “peripheral” sites like Puno placed such revolution-making promises in another light. Latin American historians of education have pointed to how national education models promoted among rural and indigenous populations from the 18th Century onward across Latin America were designed to assimilate rural and indigenous populations into the dominant social order (Perez 2009; Lopez and Kuper 2000; Lopez and Rojas 2006). Spanish literacy – rather than digital literacy – then was framed as the key to incorporating diverse minority populations, and remained so even well after nations won independence from colonial rulers. And while formal education models operated to the exclusion, depreciation, and gradual erosion of indigenous languages, by the mid-20th century they would cunningly begin to adopt bilingual instruction strategies, designed still to assimilate minority populations. By such accounts, new digital literacy initiatives were less revolutionary. Instead, merely a new means of replicating dominant approaches to education.

From the 1970s onward, such assimilationist models came under ardent critique from various indigenous movements in Peru – from el Programa de Formacion de Maestros Bilingues de la Amazonia Peruana, FORMABIAP, to la Asociacion Interetnica de Desarrollo de la Selva Peruana, AIDESEP (Perez 2009, Trapnell and Niera 2006). Together, they articulated new inter-cultural ideals that found their way into national policy in the 1990s, and continue today to sustain critical discourses for educational reforms. As Peruvian education scholar Norma Fuller writes, in the best of cases, “inter-culturidad (interculturality) extends an ethical-political proposal which seeks to improve the concept of citizenship with the aim of adding recognition of the cultural rights of people, cultures, and ethics groups.” (Fuller 2003, 10)

Indeed, drawing upon a history of intercultural activism and the development of critical approaches to dominant education models and the privileging of Spanish literacy, rural education actors working with new digital technologies similarly began to articulate new critical approaches to digital literacy promoted in state-asserted models of technology-enabled education. Their positions pressed for a distinct intercultural consciousness around technologies – articulating a form of inter-tecnologidad (inter-tecnologism) – that like inter-culturalism, aims to generate new pedagogical tools and methods around technologies, rooted in the articulation of ethical-political ideals and histories. Much like the decolonial ethics that intercultural theorists elaborated (Fuller 2003; Perez 2009; Trapnell and Niera 2006; Walsh 2004), such inter-technological ideals – as we shall see in the final section aimed to reapply intercultural histories, deploy technologies – both new and ancestral – as tools for cultural intervention, and provide alternatives to the dominant assimilationist politics embedded within national literacy and education policies.

Local Encounters: History as Resource and Interfacing with the Past

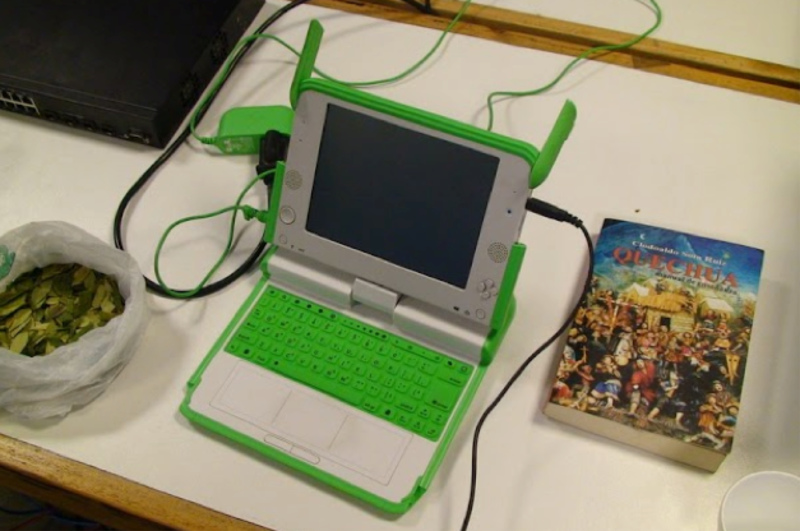

Back in Puno, Pacho’s fellow educators and colleagues were indeed volunteering their time to develop such inter-technological commitments via a software translation project – undertaken several translation hackathons they organized in Puno. During one such event held during the same week in April 2011 as a larger SugarCamp conference had been organized to discuss the XOs integration into classrooms throughout the province, they could be found meeting for days around a table that balanced an unusual mix of coca leaves, offerings to the Pachamama, and various mobile digital gadgets. During various moments in the day, volunteers would cluster into discussion circles, tossing jokes around over the imprecise translation of terms between Spanish, Quechua, and Aymara, as they worked. Their efforts drew upon the distinct expertise of an array of actors – of local teachers and programmers from Puno, Quechua and Aymara elder and youth activists, and participants of the Escuelab hack lab network from Europe and the Americas. The gathering was held in parallel with a larger 2011 Sugarcamp Conference organized by teachers in Puno – including Eleazar Mamani Pacho and Sdenka Salas around use of the XO laptop in classrooms. And by the end of the smaller translation hackathon, participants hoped to make significant headway into Quechua and Aymara software translations that could be installed onto the 1 million XOs in schools nationwide – even if the project remained independent of the state.

Laptops screens were just being opened for the workshop when Francisco Ancco Rodriguez, a native Aymara speaker, and retired public school teacher from the nearby town of Acora – called for the group’s attention. Drawing out a round bundle of cloth, he unfolded it onto the table’s surface, and spread out the dried coca leaves clustered in its center. Selecting three, [6] he arranged them into a small fan formation, and began leading a short prayer in Aymara, holding the fan of leaves – a k’intu – firmly in front of him. Just before placing the portion into his mouth, he waved the fan before him and blew a breathful of air over them [7] – and then invited the group to draw their shares from the pile.

The ritual, a ceremonial offering known in the Andes as a despacho, is one that the language activists participating in the group had seen before – although not one that most of the technology activists were accustomed to paying deference to. Long performed in Andean communities prior to auspicious occasions, the despacho is still understood as a means of communicating with the natural world’s spirits. In its most simplified version, it is framed as an offering to the Apu mountain spirits or the Pachamama – the female cosmic energy often translated as Mother Nature, but in the Andean world, associated as much with death as with birth and life. In whatever instantiation, however, it is practiced as a means of entering into a careful dialogue with ambivalent forces not fully controlled by man. Such powerful energy is read as running through varied objects in the Andean world, encompassing, as anthropologist Olivia Harris explains: “a whole spectrum of sacred beings: the mountains, the dead; untamed places such as gullies and waterfalls… The defining character of these [energies] is not so much evil or malice as abundance, chaos, and hunger… [They] are the source of both fertility and wealth, and of sickness, misfortune, and death.” (1995, 312) Such a worldview of nature and living spirits, while dramatic to untrained ears, is indeed a form of relating that is taken rather matter of factly in the Andes: as simply a living, present feature of an environment people are already in dialogue with. Rituals like the k’intu incorporated into contexts like local hackatons, then, are means of rendering both nature and technology distinctly visible and legible, and that channel multiple logics – moral, civic, and cosmological – simultaneously.

Following the Puno translation hackathon, participants pooled and shared photos of the event among themselves, across online social media platforms (as they typically would after any workshop). Their images vividly capture the diversity of actors involved in such events and working side by side, or often clustered in groups around a single computer screen. Including young indigenous language activists, Aymara and Quechua elders, public school teachers from Lima and the provinces, Latin American geeks, and Western hackers from Europe and the US, such images reflect the diversity of relations, encounters, and sentiments cultivated between participants. They demonstrate the range of diverse investments – and balance between engineering and local community perspectives – offered to build distinct technological futures by the meeting of such actors. Some elements (like the diverse arrays of mobile gadgetry) which looked comfortably familiar for anyone acquainted with hacker and geek publics before (Coleman 2011; 2013; Kelty 2005; 2008), but many of which (like the k’intu) might not have been as familiar, and invited local translations. All, however, were visually referenced as the source of some kind of positive, generative energy that compelled participation, and that marked “inclusion” as less dependent upon interaction with a particular technology, and more instead about creating new cultural and inter-relational contexts that required multiple cultural and technological lenses to be legible.

It’s notable that these kinds of visualizations are far removed from the dominant ones that circulate around OLPC, and ICT4E projects more broadly. In this vision of “digital inclusion,” what’s typically depicted is the image of the rural child in contact with a glowing laptop – often against a starkly rural or provincial landscape. [8] Rarely referenced are the diverse agents, dispersed across rural and urban sites, whose global coordinations are needed to enable local deployments. Just as no mention is made of the complexities of trans-local negotiations and cross-epistemological engagements between interest groups. Such an image of IT, prominently deployed on OLPC’s website, has traveled too to the Ministry of Education’s own publications, and to imagery circulated by technology-centered news outlets like Wired Magazine, whose June 2012 issue touted OLPC’s deployment of tablets in Ethiopia as “giving kids who had never seen a computer before [the ability to] learn quickly” (Talbot 2012).

Such images and aesthetics operate in distinct contrast to those that Puno’s hack lab participants circulate. The hybridizing aesthetics and literacies they promote, are indeed ones that echo the vanguard experiments in technology, literacy, and education that Latin American historians note have stretched back more than a century in Puno. Such local practices emerging from Puno’s altiplano explicitly challenged the Peruvian state’s turn-of-the-century vision of modernization, and the roles of educational and literacy technologies that were projected to play therein. Works by Vicky Unruh (1994), Cynthia Vich (2000), Juan Zevallos Aguilar (2002), Guisela Fernandez (2005), and Jose Garambel (2010) stress how in the early 20th Century, Puno was recognized as one of the most fervent areas for indigenist literary movements in the region. Between 1900 and 1940, diverse artists and intellectuals seeking to reframe the nation’s relationship to Indigenous culture, wrote and published numerous works that defended indigenous populations, condemned elite landowners’ usurping of lands, and insisted on new models for education and creative production that better reflected local cultural concerns and visions for the future. Literary circles like Puno’s Orkopata group, furthermore, pushed for new forms of literary expression that blended indigenous languages and narrative conventions with Castellano through the vanguard publication, Boletin Titikaka (1926-30) (Fernandez 2005; Unruh 1994; Vich 2002; Zevallos 2002).

Between the late teens and mid-1930s, in fact, vanguard literary activity was emerging all throughout Latin America (Unruh 1994). Much like those outside the continent, their activity included several possible forms: the emergence of small groups of writers, committed to creative innovation; the affirmation and dissemination of critical and aesthetic positions through written manifestos; experimentation with multiple literary and artistic genres to cut across generic boundaries; the publication of magazines as outlets for both artistic experiments and cultural debates; and the organization of study groups that generally fought against modernity’s push for cultural homogenization. What many participants noted was unique to Latin American vanguard circles, however, was their embeddedness within local contexts of deep cultural heterogeneity, and the relative proximity they had then to enable engagements and investigations into local language, folklore, and cultural history (Unruh 1994).

Puno’s Boletin Titikaka (1926-30) thus came to be known as the most lasting vanguardist magazines coming from Latin America’s own peripheral zones – and from outside major cities (Fernandez 2005; Vich 2002; Zevallos 2002). It grew in fact, to have a readership not only across Peru, but across Latin America and globally – reaching as far as Lima’s best known vanguard publication, Amauta. It was known for articles on “aesthetic Indoamericanism,” and The Boletin’s editor, the surrealist writer Gamaliel Churata devoted extensive attention to linguistic investigations in essays and bilingual poetry using vernacular verse. The magazine promoted the results of such studies, and indigenist orthography more generally, with the goal of making written Spanish appear visually like a more phonetic transcriptions of Quechua or Aymara. Thus alternative spellings of various Spanish phrases commonly appeared. Such practices, as literary historian Vicky Unruh writes, were meant to “liberate aesthetics from chains of tradition” (1994, 210) reproduced through the politics of language and technologies of literacy. Conventions in Grammar and genre were seen as adhering to problematic politics and “blocking ‘true consciousness’”… The artist’s work, Unruh elaborates, was thus to “forge new creative, and technical principles for language” that were inventive as well as able to recover lost languages from national and ethnic pasts. [9] As she continues, “Given that to write and speak well signified privilege and functioned as keys to social mobility, the vanguards recuperative linguistic undertakings constitute a pragmatic rapprochement between the language of literature and the language of everyday life and underscore language’s complicity in social conflict.” (1994, 210)

Other Punenan indigenists of the era worked specifically through educational models to challenge what they saw as the state’s problematic application of literary technologies and educational models as a means to reform indigenous populations. Beginning of the 20th century, the Puno educator and intellectual Jose Antonio Encinas, issued some of the earliest national proposals for a model of indigenous education rooted within native culture (Garambel 2010). Encinas criticized the imposition of a system which he saw as operating on the principle that – as he described it: “everything native should be forgotten.” He critiqued how state officials often saw indigenous dance and music to be of “poor taste” – how municipalities prohibited indigenous communities from maintaining traditional dances, and how police were allowed to punish and fine Indians that entered restricted urban areas. He thus wrote: “If we educate students about Dante and Shakespeare – why not allow them all to sing the excellences of the races and beauties of the altiplano?” His proposals eventually helped to push forth new state policy – the first on bi-lingual education – in the 1940s that recognized that Peru’s two largest indigenous languages, Quechua and Aymara, should be used in class instruction. [10]

Finally, the artists and educators of Puno’s vanguard movements of the early 20th century, influenced the founding of one of the Warisata schools just outside Puno’s borders, in the Bolivian town by the same name (Gustafson 2009; Perez 1962; Salazar 1997 2005). Founded in 1931 as a collaborative project between local Aymara community leaders and progressive Andean educators, it saw itself as a radical experiment in indigenous education and education through collective uses of technology. Education at the Warisata was seen as a key means of recuperating indigenous territory and expressing collective rights. Thus, the school didn’t mimic Western or Limenan models, but was based on indigenous community structures, with a council of Aymara elders – the Parlamento Amauta – that oversaw it and maintained contact with local leadership; and technologies that were applied for both educational and communal purposes, through classes structured around agricultural and community-based production in weaving and ceramics. From its beginnings too, the school attracted global attention of diverse intellectuals, artists, writers, and journalists from both in and outside Latin America. Peruvians like Gamaliel Churata would be involved with the Bolivian school from 1932 onward, bringing other writers, artists, intellectuals and journalists from the region with him. [11] And its founding would compel the organizing of the first Interamerican Indigenist Congress in 1945. Held at the Warisata’s rural site, it attracted politicians and education leaders from across Latin America, with participation from the governments of Perú, Bolivia, Ecuador, Mexico, Guatemala, Venezuela, Colombia, and Cuba (Perez 1962; Salazar 1997 2005). [12]

Today, some 17 Latin American countries (López and Küper 2000, 4) apply models of Intercultural Bilingual Education (IBE) – an achievement that builds on the beginnings of rural education activists and reformers’ agendas from nearly a century ago. Moreover, the legacy of such regional education activists and inter-cultural reformers is reflected in the work of Puno’s hack lab participants, whose book shelves and workshop tables feature key works and publications from turn of the century intellectuals of the Altiplano, including Churata, Encinas, and Warisata’s founders, and contemporary histories written on the like. Mentors for Escuelab Puno’s teachers and engineers alike include some of the region’s best known historians on intercultural and indigenous activism – from historians like Jose Garambel, to family members and archive keepers of Gamaliel Churata, to the Aymara artists Peruko Ccopacatty. Such archival practices and inter-generational references by Puno’s hack lab participants demonstrate the diverse cultural resources that are used in their work to generate visions of new and “alternative futures.” Their efforts delink the associations entrenched by dominant ICT4E visions of the periphery as locked within part and static traditions, and urban innovation and engineering centers (whether MIT or Silicon Valey) as the lone sites of innovation and future making. That such engagements might have escaped the historical conceptions of elite engineers and designers from global projects like OLPC – for as globally hyper-connected, information-rich, and structurally resourced as they might be, indeed – is what is may deserve further study.

Conclusion

Indeed, despite OLPC’s promotion by highly resourced and high profile Western engineers and design circles – that included support from such elite IT corporations as Google, Red Hat, and the chip maker AMD (Andersen 2011) – as well as by the Peruvian state and global governing bodies, it was not received with an uncritical embrace among Puno’s rural technology collectives and local hack lab networks. Neither, however, did their orientations whole-heartedly reject OLPC as an unworkable option for provincial communities. Rather, the work of rural hack lab spaces like Escuelab Puno aimed to create more balanced, multi-disciplinary partnership around ICT4E deployments that cultivated alternatives through historically informed engagements with technology. Activities included co-organizing annual workshops with local teachers, other FLOSS advocates, and indigenous language activists to discuss XO integration into local schools, and then sought to bring OLPC into closer interface with local communities and experts. Their work, that is, aimed to counter the selective and narrowly construed set of narratives around technological futures that disproporionately underscored the “key” role of engineers, technology designers, or IT corporates while underplaying or even ignoring other kinds of actors working around new technological deployments. They underscore too how central to what hack labs can extend to local communities is not simply access to new technological resources, but access to cultural and historical resources that aid the social organizing and extension needed to ground such resources in community life and social histories.

Such approaches counter the techno-fundamentalist ethos that commonly underpins the most ambitious of ICT4E projects, and that operates less by acknowledging the value and resource of local histories than by making pronounced projections of the promise of future change (even when in direct contradiction of existing evidence or records). And yet, despite their critique of techno-fundamentalist frameworks around technology, the practices of Peru’s rural hack labs underscore how they do not read the alternative as being only to retreat to relativistic isolation where no means of trans-local or global connection around digital networks could be imagined. The question they seem to pose instead is whether a more conscientious, humbled versions of global digital collaborations can be recovered for our networked age that acknowledges, as numerous science studies scholars from Arturo Escobar (2007; 2008) and Donna Haraway (1991; 1997) to Ivan da Costa Marques (2005) and Bruno Latour (1987; 1993; 2010) have underscored, how knowledge practices are always local, situated, and social. Rural hack lab practices – that bridge generations, urban and rural imaginaries, indigenous leaders with global hackers, and ethics pushing towards the future with others remembering an obligation to honor the past – push for such possibilities. The events they generate, while not urging for either outright technological revolution or rejection – might be read instead as creating spaces of “awkward engagement,” as anthropolgist Anna Tsing framed the term. They signal the possibility of a space where distinct forces and interests meet in a “zone of cultural friction” – one where consensus and the dissolution of difference can’t be taken for granted – and “where words [may] mean something different across divides even as people speak.” (2004, xi)

Such mixed scenes suggest something more than a simple critique of dominant framing of technological fundamentalism. Here, actors work around the possibility of activating what Tsing called “engaged universals” instead (Tsing 2004, 8). Such forms acknowledge the dual opportunity and challenge they bear as bodies of “knowledge that move” (Tsing 2004, 7) across space and time. As such, they have the capacity to construct new bridges between sites of encounter – but to also foreclose other interfaces if not conscientiously activated. And here, then, a considered treatment of local histories and the past must be surely faced, even when more than a few episodes of conflict, betrayed trust, or long standing tension are involved. Dipesh Chakrabarty emphasized this in reminding his readers that universals could be called upon to do multiple kinds of work – among them, to serve as “a necessary placeholder in our attempt to think through questions of modernity.” Likewise, ICTs in their globalizing assertions might be said to be a means for us to think through questions of futuricity, unstable though such projections may be, and filled at once with pitched hopes for new prospective relations, as well as other ways to frame those past.

Endnotes

[1] Aymara is still spoken by an estimated 41 percent of Puno’s 1.3 million inhabitants, and Quechua spoken by some 30 percent.

[2] He would later be sought out for interviews from global news outlets, including the US’s National Public Radio and the Christian Science Monitor.

[3] Similar findings have emerged too around MOOC platforms like Udacity, which have enrolled hundreds of thousands of students in low-cost courses worldwide, but which studies found produced lower pass rates of 20% to 44% for university courses that had typically seen 75% student pass rates. (Anders 2013).

[4] That such actors were effectively framed as impediments to “real” learning, was reflected further in OLPC’s mission statement, which contrasted images of existing classroom experiences to the change the XO experience offered: “[We aim] to create educational opportunities for the world’s poorest children by providing each child with a rugged, low-cost, low-power, connected laptop with content and software designed for collaborative, joyful, self-empowered learning. When children have access to this type of tool they get engaged in their own education. They learn, share, create, and collaborate. They become connected to each other, to the world and to a brighter future.”

[5] In the case of Plan Huascaran, the national digital education initiative in Peru launched under then President Alejandro Toledo’s administration, that preceded the state’s OLPC investments.

[6] The darkest, shiniest leaves that show the least signs of age, mold, or blemishing are typically selected.

[7] This act, known as the pikuy, is that which is thought to allow the invocation of spiritual beings.

[8] The familiar vision the computer-ready child that modern audiences have come to recognize as indicative of future-readiness remains stable, that is, except for the rural setting.

[9] One of the most celebrated literary works of the period – the novel El Pez de Oro, was written by the Boletin Titikaka’s founder, Gamaliel Churara, and offered an exemplary model of experiments in linguistic pluralism to this end. It demonstrated a vibrant mixing Quechua, Aymara, and Spanish together to reflect the cultural heterogeneity and sometimes fragmentedness of the region.

[10] And his ideas also took form in establishing La Escuela Nueva in 1907, the first public school to be officially of indigenist orientation – in Puno. Encinas’ work was in many ways built on the tradition of La Escuela de Utawilaya, founded in 1898 as a clandestine school that operated by night to teach Aymara Indians to read, and run by the Aymara community member, Manuel Z. Camacho an Camacho, after having participated in regional protests against the abuses of local landowners with Aymara leaders from nearby Puno towns – decided to create a space where peasants could acquire reading and literary skills as “instruments of freedom.” (Garambel 2010) Despite the acts of violence and arrests he withstood, Camacho kept the school running until 1909. By 1918 some 45 primary schools run by Aymara Indians had formed in Plateria.

[11] Various Bolivian and Mexican intellectuals were involved with the project, as was the North American writer and anarchist Frank Tanenbaum. And Puno-based writers and educators like José Antonio Encinas were among Peru’s best known friends and visitors to the project. And Gamaliel Churata’s own ties to the site are reflected in the art work of El Pez de Oro, which was drawn by Warisata teacher Carlos Salazar.

[12] Multiple participating nations in would develop educational polities based on the recommendations of the Congress. By 1939, some 16 additional indigenous-run schools had been founded across Bolivia alone.

References

Anders, G. 2013. “Udacity’s San Jose Stumble: The Perils Of ‘Failing Fast.’” Forbes. July 19. Available at: http://www.forbes.com/sites/georgeanders/2013/07/19/udacitys-san-jose-stumble-the-perils-of-failing-fast [Accessed May 5, 2014]

Andersen, L. 2011. “A Travelogue of a Hundred Laptops.” Masters Thesis, Aarhus University.

Bajak. F. 2012. “Peru’s Ambitious Laptop Program Gets Mixed Grades.” The Associated Press. Available at: http://bigstory.ap.org/article/perus-ambitious-laptop-program-gets-mixed-grades [Accessed May 5, 2014]

Chan, A. 2004a. “Coding Free Software, Coding Free States: Free Software Legislation and the Politics of Code in Peru,” Anthropological Quarterly, 77, 3: 531-545.

——-. 2004b. “Seeing Free Software, Seeing Free States: Free Software Legislation and the Politics of Code in Peru.” Anthropological Quarterly, 77, 3.

——-. 2014. Networking Peripheries: Technological Futures and the Myth of Digital Universalism. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

——-. Forthcoming. “Balancing Design: OLPC Engineers and ICT Translations in the Andes.” In E. Medina, da Costa Marques, I., and Holmes, C., Eds. Beyond Imported Magic, MIT Press.

Chakrabarty, D. 2000. Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Coleman, G. 2011. “Anonymous: From the Lulz to Collective Action.” The New Everyday, March 2011. Available at: http://mediacommons.futureofthebook.org/tne/pieces/anonymous-lulz-collective-action. [Accessed Feb. 1, 2012]

——-. Coding Freedom: Hacker Pleasure and the Ethics of Free and Open Source Software. 2013. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Cristia, J. 2012. “One Laptop per Child in Peru: Findings and the Road Forward.” IDB Blogs. Feb. 28. Available at: http://blogs.iadb.org/education/2013/02/28/one-laptop-per-child-in-peru-findings-and-the-road-forward/ [Accessed May 1, 2013]

Cristia, J., Ibarrarán, P., Cueto, S., Santiago, A., Severin, E. 2012. “Evidence from the One Laptop per Child Program.” Washington, DC: International Development Bank.

da Costa Marques, I. 2005. “Cloning computers: From rights of possession to rights of creation.” Science as Culture,14: 139-60.

de la Pena, C. 2006. “’Slow and Low Progress,’ or Why American Studies Should Do Technology,” American Quarterly 58, 3: 915-941.

Escobar, A. 2007. “Worlds and Knowledges Otherwise: The Latin American modernity/coloniality research program,” Cultural Studies, 21, 2: 179-210.

——-. 2008. Territories of Difference: Place, Movements, Life, Redes. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Fernandez, G. 2005. American Anguish: The Literature and Journalism of Gamaliel Churata. Lima, Peru: Editorial San Marcos.

Fuller, N., ed. 2003. Interculturidad y Poliitca. Desafios y Posibilidades. Lima, Peru: Red para el Desarrollo de Ciencias Sociales en el Peru.

Garambel, J. 2010. Las Luchas por la Escuela In-Imaginada del Indio: Escuelas, Movimientos Sociales, e Indigenismo en el Altiplano. Puno, Peru: Universidad Nacional del Altiplano.

Gustafson, B. 2009. New Languages of the State: Indigenous Resurgence and the Politics of Knowledge in Bolivia. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Haraway, D. 1991. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective,” In Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. New York; Routledge.

———-. 1997. Modest_Witness@Second_Millenium: FemaleMan_Meets_Oncomouse. New York: Routledge.

Harris, O. 1995. “The Sources and Meanings of Money: Beyond the Market Paradigm in an Ayllu of Northern Potosi,” in Ethnicity, Markets, and Migration in the Andes: At the Crossroads of History and Anthropology, Larson, Brook & Olivia Harris, eds. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Jacobsen, N. 1993. Mirages of Transition: The Peruvian. Altiplano, 1780-1930. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Kelty, C. 2005. “Free Science.” In J. Feller, B. Fitzgerald, S. Hissam and K. Lakhani, eds., Perspectives on Free and Open Source Software. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

——-. 2008. Two Bits: The Cultural Significance of Free Software. Chapel Hill, NC: Duke University Press.

Latour, B. 1987. Science in Action. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

——. 1993. We Have Never Been Modern. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

——. 2010. On the Modern Cult of the Factish Gods. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Lopez, L. and Kuper, W. 2000. “Intercultural Bilingual Education in Latin America: Balance and Perspectives.” Available at: http://www2.gtz.de/dokumente/bib/00-1510.pdf [Accessed May 1, 2013]

Lopez, L. and Rojas, C., eds. 2006. La EIB en America Latina Bajo Examen. La Paz, Bolivia: Plural Editores.

Medina, Eden, da Costa Marques, Ivan, and Holes, Cristina. Forthcoming. Beyond Imported Magic. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

Negroponte, N. 2009. “Lessons Learned and Future Challenges.” Speech, Reinventing the Classroom: Social and Educational Impact of Information and Communication Technologies in Education Forum, Washington, DC: September 15. Available at: http://www.olpctalks.com/nicholas_negroponte/ [Accessed May 1, 2013]

——–. 2010. “Laptops Work,” Boston Review, 35(6). November/December 2010. Available at: http://bostonreview.net/BR35.6/ndf_technology.php. [Accessed May 1, 2013]

Oppenheimer, A. 2012. “Region’s One Laptop Per Child Plan Has a Future.” Miami Herald. April 30. Available at: http://www.recordonline.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20120430/OPINION/204300311&cid=sitesearch [Accessed May 1, 2013]

Perez, S. J. 2009. “Intercultural Bilingual Education: Peru´s Indigenous Peoples´ Answer to Their Educational Needs.” Indian Folklife, 32: 14-20.

Perez, E. 1962. Warisata; La Escuela-Ayllu. La Paz, Bolivia: Hisbol/CERES.

Salas, S. 2009. La Laptop XO en el Aula. Puno, Peru: Sagitario Impresores.

Salazar, C. 1997. “La Escuela Ayllu y las Concepciones Educativas de Elizardo

Pérez.” Warisata Mía. La Paz: Editorial Juventud.

——–. 2005. Gesta y Fotografia: Historia de Warisata en Imagenes. La Paz, Bolivia: Lazarsa Ediciones.

Santiago, A., Severin, E., Cristia, J., Ibarrarán, P., Thompson, J., and Cueto, S. 2010. “Evaluacíon experimental del programa ‘Una Laptop por Niño’ en Perú.” Washington, DC: Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo. Available at: http://www.iadb.org/document.cfm?id=35370099 [Accessed June 1, 2011]

Severin, E. and Capota, C. 2011. “One-to-One Laptop Programs in Latin America and the Caribbean.” Washington DC: International Development Bank. Available at: http://idbdocs.iadb.org/wsdocs/getdocument.aspx?docnum=35989594 [Accessed May 1, 2013]

Smith, M. and Marx, L. 1994. Does Technology Drive History? The Dilemma of Technological Determinism. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Talbott, D. 2008. “Una Laoptop Por Nino,” Technology Review Magazine, June.

Talbot, D. 2012. Given Tablets but No Teachers, Ethiopian Children Teach Themselves. MIT Technology Review. October 29. Available at: http://www.technologyreview.com/news/506466/given-tablets-but-no-teachers-ethiopian-children-teach-themselves/ [Accessed May 1, 2013]

Toyama, K. 2010. “Can Technology End Poverty?” Boston Review, 35(6):12-18, 28-29. November/December 2010. Available at: http://bostonreview.net/BR35.6/ndf_technology.php [Accessed Jan. 4, 2011]

——–. 2011. “There Are No Technology Shortcuts to Good Education,” EdutechDebate.org. Available at: http://edutechdebate.org/ict-in-schools/there-are-no-technology-shortcuts-to-good-education/ [Accessed May 1, 2013]

Trapnell, L. and Niera, E. 2006. “La EIB en el Peru.” In Lopez, Luis Enrique and Carlos Rojas, eds. La EIB en America Latina Bajo Examen. La Paz, Bolivia: Plural Editores.

Trucano, M. 2012. “Evaluating One Laptop Per Child (OLPC) in Peru.” World Bank Blogs. March 23, 2012. Available at: http://blogs.worldbank.org/edutech/olpc-peru2 [Accessed May 1, 2013]

Tsing, A. 2004. Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Twist, J. 2005. “UN debut for $100 laptop for poor,” BBC News. November 17. Available at: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/technology/4445060.stm [Accessed May 1, 2013]

Unruh, V. 1994. Latin American Vanguards: The Art of Contentious Encounters. Berkeley, CA: Univ. of California Press.

Vaidhyanathan, S. 2006. “Rewiring the ‘Nation’: The Place of Technology in American Studies.” American Quarterly 58, 3: 555-567.

——–. 2011. The Googlization of Everything (And Why We Should Worry). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Vich, C. Indigenismo of the Peruvian Vanguard. Lima, Peru: Pontificia Universidad Catolica del Peru: 2000.

Villanueva, E. 2011. The Importance of Being Local. The European Magazine. April 28. Available at: http://www.theeuropean-magazine.com/256-villanueva-masilla-eduardo/255-ict-in-development-cooperation [Accessed June 1, 2011]

Walsh, C. 2004. “Geopoliticas del Conocimiento, Interculturalidad, y Descolonizacion”

Warschauer, M. and Ames, M. 2010. “Can One Laptop per Child Save the World’s Poor?,” Journal of International Affairs, 64, 1.

Winner, L. 1989. The Whale and the Reactor: A Search for Limits in an Age of High Technology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Zevallos, J. 2002. Boletin Titikaka: Indigenismo and Nation. Lima, Peru: Instituto Frances.J