Keywords:

Keywords: Internet-of-things, Internet architecture, network commons, DRM, remixing, 21st century ownership, privacy, digital feudalism

By James Losey and Sascha D. Meinrath

Introduction

The strength of the Internet, and the foundation for many of the most transformative digital innovations of the last quarter century, has been its openness. Open architectures, open protocols, and open source software have supported continuing innovation and creative destruction (Schumpeter, 1942); however, contemporary business practices are shifting us away from this historical precedent and instituting ever-increasing centralisation of control over communications technologies. In turn, these hierarchies are limiting the extensibility of technology and foreclosing on the potential for Digital Craftspersonship in the 21st Century. Tinkering has long been a part of a thriving digital ecosystem—early hackers turned to computers to improve the complex timing of model trains, while later innovators developed new products in their garages and created hobbyist communities and networked experimentation that drove the transformation of the mainframe computer industry and gave rise to the personal computer (Levy, 2001). The Internet, an output of an academic-military research project to develop a robust communications network, pioneered critical changes to previous communications technologies—as examples, anyone could offer a service over the network, the service could be accessible by anyone on the network, and offering an application or service did not require the permission of network operators (Lessig, 2002; Zittrain, 2008).

Fundamentally, this “permissionless” Internet supported the craftspersonship that has defined the innovative ideal of the Internet: The freedom for those with desire and skill to innovate and adapt technologies to create new forms and functions. Unfortunately, while the open and decentralised nature of the Internet has supported this rapid evolution of useful tools and the growth of new markets, the shift toward command-and-control networking has created substantial barriers for end-user innovation (Lessig, 2002; Zittrain, 2008; Meinrath et al., 2011). Changes in network management processes and agreed-upon networking and interconnection standards, locked hardware devices and acceptable-use restrictions severely limit how end-users can engage with and adapt today’s networked technologies (Zittrain, 2008; Meinrath et al., 2010).

As networked computers become increasingly commonplace and integrated into ever more objects, the locus of control over these computing devices is pivotal to how users can engage with these consumer goods and products. This interconnection of devices was described as an “Internet of things” by Ashton in 1991 (Ashton, 2009) and has become a conceptual framework that undergirds contemporary regulatory discourse in the United States and Europe (Federal Trade Commission, 2013; European Commission, n.d.). Optimistic scholars have focused on the positive potentials of the growth of the Internet-connected society—from the new power balances of the information-network mediated society (Castells, 2009, 2010) to the support of long-tale markets (Anderson, 2008) and the potential of commons-based peer-production afforded by digital networks (Benkler, 2006). Other authors have offered more critical perspectives on the implications of purely profit-driven motivations in the development of networked platforms (McChesney, 2013; Fuchs, 2011a), and the trend for communications technology to shift from the open tools of tinkerers to the closed technologies of monopoly enclosure (Wu, 2011). Flanagin et al. (2010) problematise the “code” of the Internet as a social construct that influences the actions and activities of users, though fall short of engaging with the question of tensions between different layers of the Internet’s architecture. This article investigates how the shift towards centralised control of computer-enabled devices provides a mechanism for commercial and political interests to utilise a hierarchical technology stack to limit innovation by end-users.

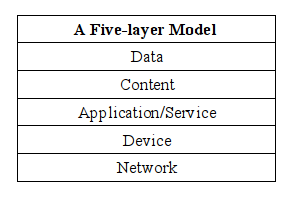

This paper offers an innovative approach—a technologically-focused analysis of the relationships between the actors and technologies that have created a global “network of networks” and the devices, services and applications supporting Internet-mediated content and relationships. Rather than focus solely on the role of “Internet of Things” technologies, this paper adopts the normative framework that the Internet is a global connector of actors and analyses the impact of the tensions of five conceptual layers of this global network. Our analysis positions the Internet as mediator of networked relations and focuses on the potential relationship of users to the Internet as an increasingly ubiquitous tool. This framework provides a new methodology for examining how the locus of control supports and/or undermines craftspersonship across five dimensions of networked information and communications technology (ICT): networks, devices, applications/services, content and data. We apply this framework to secondary source material including news articles and recent research. We document how the lock-down of technologies and centralisation of control change the relationships between users and digital tools, as well as how the limitations to Digital Craftspersonship hamper creativity, lessen the power of the Internet in social movements, undermine the emergence of meaningfully competitive markets, and lead to less liberatory opportunities for Netizens around the globe.

The Digital Craftsperson

The networking of everyday objects—from thermostats to cars and home appliances, to toys—begs the question: Do these computing devices enable end-users innovation or serve as centrally controlled constraints? Key work has also highlighted the regulatory shifts that have supported enclosures of specific aspects of the Internet, such as networks (Lessig, 2002; Meinrath et al., 2010), devices (Lessig, 2006; Zittrain, 2008) and content (Lessig, 2008). Although Benkler (2006), Lessig (2002) and Zittrain (2008) develop a fairly adept technical analysis, Palfrey and Zittrain note that greater understanding of the architecture of technology is needed within the literature (Palfrey and Zittrain, 2011), and that previous research does not fully incorporate the implications stemming from the change of locus of control over data from end-users to intermediaries. We posit that different technological layers can be leveraged for political or commercial interests to limit functionality and innovation across the entire technology stack. As this paper illuminates, the mechanisms of control over these networks are creating a relatively locked network of pre-defined, static objects, rather than a flourishing global digital ecosystem that supports the tinkering, hacking and new forms of Digital Craftspersonship that will create more liberatory future innovations.

This paper posits “craftspersonship” as a Weberian ideal of the Internet user (Weber, 1947; Cahnman, 1976). Although not every user will necessarily offer innovations, and not at all times, the potential for craftspersonship defines the innovative potential of the Internet and offers a framework for understanding the implications of the architecture of networked systems. Sennett argues that craftspersonship emerges from the human desire to do something well, and combined with skill and sufficient control of a medium, drives a user to transform and adapt it (Sennett, 2008). Thus, in much the same way that a carpenter imagines lumber as a chair, the open-source developer imagines adapting and improving upon the functionality of a software application (Ibid.); the Digital Craftsperson reimagines the functionality and potential of different components of the Internet. Where a potential craftsperson may have skill and desire, limited only by their competency with the material in question, with digital technologies, a craftsperson’s freedom to tinker can be limited by the architecture of the Internet, as well as additional digital control planes (Galloway, 2004; Lessig, 2002; Zittrain, 2008; Meinrath et al., 2010). Thus, while one perspective of the study of technology views the user as a major influencer on the final design of a product (e.g., Bilker, 1996), investigating the barriers to craftspersonship offers a renewed focus on the often-subtle enclosures undermining the adaptability of digital technologies (Winner, 1986; Jasanoff, 2006; Meinrath et al., 2010). This latter perspective offers a more technologically-nuanced and sophisticated approach to understanding how centralised control introduces new forms of commercialisation and governmental intervention in the future Internet of Things.

Telecommunications scholars have often viewed the Internet as a form of commons and a dialectic to investigate constraints and enclosures (Lessig, 2002; Benkler, 2006; Meinrath et al., 2010). The potential of an Internet commons stems from its open architecture: A standardised, open Internet Protocol that supports the interconnection of networks owned and operated by different actors around the globe, with an extensible functionality supporting a diverse array of services and applications ranging from the World Wide Web to email, messaging, media sharing and games. The Internet’s “hour-glass architecture”, with a single open protocol interconnecting a diverse array of services and applications running over myriad different physical infrastructures, has traditionally allowed end-users to define how they use the Internet—especially the sharing of innovations without permission (Deering, 2001; Lessig, 2002).

The architecture of the Internet and the code used within a technology are mechanisms for control (Lessig, 2008), and a shift towards closed systems have already resulted in new forms of technological enclosure (Meinrath et al., 2010). These shifts towards closed systems are often driven by financial or political motivations. Mosco defines commmodification as “the process of transforming use values into exchange values, of transforming products whose value is determined by their ability to meet individual and social needs into products whose value is set by what they can bring in the marketplace” (Mosco, 1996: 143-144). Private actors may seek to change networking protocols and develop new revenue streams based on specific types of network traffic (e.g., video, telephony). Governments may seek to centralise architectures in order to more easily restrict specific types of content. The analytical framework presented in this article illuminates how centralised control at any one layer can be sufficient to limit activities of the other layers composing a technology stack and restrict the range of innovation possible by end-users. Focusing on the crafterperson offers a dialectic for critical analysis to investigate the various layers and identity how shifts in the locus of control within each can introduce unexpected technological constraints.

This framing builds from Zittrain’s (2008) framework of generativity, in which a third-parties and end-users can develop and build upon a device or network. Examples of generative norms include the end-to-end principle of the Internet and the rise of the personal computer (which has traditionally be comprised of a highly extensible platform that interoperates with a diverse array of different components). Generativity relies on common standards that encourage flexibility within the other layers in a technology stack, such as the Internet Protocol and operating system of a computer. Van Schewick describes the alternative as integrated architecture that restrict changing or modifying other layers (Van Schewick, 2010: 125).

Digital Craftspersonship offers an expansion on the concept of generativity, one focused on the behaviour of the individual in relation to a technology, rather than the technology itself. As the framing of the “Internet of Things” begins to permeate policy discussions, understanding the nuances of the interactions between users and technologies and developing a framework for analysing networks of human actors encompassing a range of relationships to technology, is critical. The “Digital Craftsperson” frame describes an ideal-type relationship: The potential for actors to act with full locus of control over the technologies they use. Digital Craftspersonship assumes that individuals desire to do something well, and embodies the potential for entrepreneurial action, the power to innovate, and the freedom to control technologies for ones own purposes. However, this relationship is shaped by the tensions between different components of a networked system, including the networks, devices, applications/services, content, and data that the Digital Craftsperson interacts with. Documenting the interactions amongst these components requires a framework that documents both the architectures and control planes of networked systems (Palfrey and Zittrain, 2011).

A five-layer analytical framework

The politics and tensions of digital technologies like the Internet can be illustrated by distinguishing amongst the different conceptual dimensions, or layers, of the system. Each layer participates in a hierarchical stack, providing services to the layers above while depending on the layers below (Burns, 2003). However, different authors provide different frameworks for analysis of the Internet. For example, one early conceptualisation is the Department of Defense (DoD) Model, a four-layer model that separates three categories of protocols from physical connections (Burns, 2003). The widely-adopted, seven-layer, Open System Interconnection (OSI) model offers a more nuanced stack that focuses on the interoperability and extensibility of the Internet. The seven layers distinguish between three media layers (i.e., physical, data link and network) and four hosts layers (i.e., transport, session, presentation and application). In the OSI model, the application layer refers to network protocols that facilitate networked services, such as DNS for web browsing, or SMTP and IMAP for email, rather than the services themselves. However, by focusing on the networking elements, these approaches exclude analysis of other components of the system, such as interconnected devices or the role of digital/social media platforms.

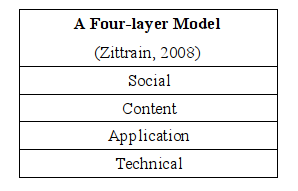

In order to expand the scope of inquiry to include services supported by digital networks, some scholars have condensed the seven layers of the OSI model into one or two layers and including additional layers to the top of the stack. Lessig (2002) offers a three-layer model that condenses the OSI model into a physical, code and content framework. Benkler (2006) similarly uses a three-layer model, with a logical layer providing the functionality of Lessig’s code layer. Zittrain (2008) adapts this model, combining the physical and logical (or protocol) layer into a single layer and adding application and social layers. The application layer represents “the tasks people want might want to perform over the Internet”, such as email, viewing video or messaging (Zittrain, 2008: 68). These approaches simplify observations of the networking layer, while offering a lens to analyse tensions between network routing with physical infrastructure and distribution of content.

This paper offers a five-layered approach building on Zittrain’s model. The five technological layers include an undergirding, lowest layer (the technical layer for Zittrain, and the physical layer for Lessig and Benkler), which we call the network layer, in keeping with its function. We also introduce a device layer as the second layer, between the “network” and “application” layers, since unlike traditional computers, contemporary devices (from cell phones to coffee makers) are no longer neutral platforms, but rather control points that interact with and directly shape people’s computer-mediated experiences.

This paper offers a five-layered approach building on Zittrain’s model. The five technological layers include an undergirding, lowest layer (the technical layer for Zittrain, and the physical layer for Lessig and Benkler), which we call the network layer, in keeping with its function. We also introduce a device layer as the second layer, between the “network” and “application” layers, since unlike traditional computers, contemporary devices (from cell phones to coffee makers) are no longer neutral platforms, but rather control points that interact with and directly shape people’s computer-mediated experiences.

In addition, above the more traditional application and content layers (which we adopt as our layers nos. 3 and 4), we posit that a data layer is crucially important. Security technologist Bruce Schneier characterises data as “the exhaust of the information age” (Schneier, 2015: 17) and that can include everything from a user’s locations, driving speeds, travel and purchase habits, personal contacts, Internet history, and an ever-increasing array of personal identifying information. As discussed by Losey (2015), this data layer encompasses “the captured information of human interaction with the underlying technology stack” and allows for the analysis of data that is collected, transmitted and stored as part of end-users’ interactions with digital technologies.

These five technical layers support the overarching social layer—activities and interactions facilitated by digital networks—and this model provides a rich framework for analysing how locus of control over the network, device, application/service, content and data layers impact the range of interaction with that layer, and amongst and between layers.

These five technical layers support the overarching social layer—activities and interactions facilitated by digital networks—and this model provides a rich framework for analysing how locus of control over the network, device, application/service, content and data layers impact the range of interaction with that layer, and amongst and between layers.

Although a potential Digital Craftsperson may have the skill and desire to innovate at a given layer, the generativity of a layer can be constrained by actors controlling that given layer or by those below it. The critical characteristic of a layer that supports craftspersonship is a decentralised locus of control at the edges of the networked system, which results in end-users and innovators not needing permission for the devices or applications they use, the content they view, to control their personal data, or to tinker with the underlying technology stack. However, as we document, contemporary technological and legal constraints are instead establishing centralised control and restricting how users can interact with each specific layer. The following section examines several exemplars of this locus of control shift across our five-layer model and analyses how this centralised control creates barriers undermining innovation by Digital Craftsmen and Craftswomen.

Constraining Digital Craftspersonship

We now turn our attention to exploring several exemplars where Digital Craftspersonship is being detrimentally impacted via centralised control and lock down. These examples illuminate how commercial or political motivations are able to leverage constraints in order to restrict how today’s computerised objects function, and how our 5-layer model helps capture nuances in this command-and-control that are currently not well explicated.

Networks: Forced scarcity

The unique architecture of the Internet allows the interconnection of hundreds of millions of networks around the world and supports a plethora of applications and protocols. This network layer architecture demonstrates how a common open Internet Protocol (IP) facilitates the connectivity of numerous networks, while supporting diverse functionality and offering widespread interoperability (Deering, 2001; Burns, 2003; Zittrain, 2008). The Internet’s end-to-end design principle supports applications on the edges of networks and was posited as a break from traditional mainframes and their centralised control (Saltzer et al., 1981). For the first decades of the Internet, this open architecture was a marked departure from the centralised control of telephony in which control over wireline infrastructure was used to restrict what devices users connected to their phone lines or how mobile operators charged orders of magnitude different prices for the transfer of bits for telephony vs. simple messaging service (SMS) traffic. However, network operators have been systematically moving away from these open, decentralised norms and introducing artificial scarcity to the flow of information. As a result, these same operators are able to monetise specific uses of applications, services, or communications, leveraging control over networks to limit functionality on higher layers of the stack.

As the explosion of innovations utilising unlicensed Wi-Fi exemplifies, access to electromagnetic spectrum allows for network craftspersonship by facilitating enormous new avenues for tinkering and developing innovative edge technologies (De Filippi and Tréguer, 2014). Utilising two small bands of unlicensed spectrum, at 2.4 GHz and 5.8 GHz, Wi-Fi has not only expanded the reach of Internet access, but also the business models used for broadband service provision, from distributed mesh networks spanning entire cities to in-home audio distribution systems. A 2014 study by Telecom Advisory Services estimated that Wi-Fi contributed US$ 222 billion to the U.S. economy (Katz, 2014); however, despite the massive potential of increased unlicensed spectrum, over 95% of the public airwaves in the United States (under 30 GHz) are either reserved for governmental use or licensed to private parties, and largely sit unused [End Note #1]. Despite the development of spectrum-sharing and cognitive radio technologies, the regulatory approach to spectrum has remained mired in early 20th Century thinking, resulting in the creation of massive artificial scarcity. Given severely limited access to the public airwaves and the increasing ease of access to software-defined radios, contemporary radio innovators are likely to become electromagnetic jaywalkers who are technically breaking the law, yet highly unlikely to be prosecuted.

Furthermore, in contrast to the open and flexible use of Wi-Fi, Internet Service Providers (ISPs) are increasingly seeking ways to leverage their control over network resources to introduce false scarcity over Internet communications. The most recent example of which is the implementation of broadband caps on broadband service—in essence, limiting how much data a customer can transfer in a given period of time in order to create new pricing tiers based upon customers having to pay for the maximum amount of data they might ever use. Effectively, this represents a shift in billing structure for broadband service from a flat rate to usage-based pricing (though users are rarely refunded for using less than their allotment).

The use of data caps impose a false scarcity on data networks and is neither dependent on network costs, nor used for reasonable network management. Ostensibly, the use of data caps serve as a remarkably blunt instrument to reduce overall usage of a network’s capacity resources and encourage customers to purchase or retain television services. In reality, data caps are an explicit effort to create a scarcity of bytes, impact the types of services customers use via their Internet connections, and commercialise services that otherwise would not gain market share by explicitly excluding them from data cap metering. Minne (2013) argues that data caps on wireline Internet access are intended to ensure that users can “complement, but not replace, traditional subscription TV services,” which makes sense when so many ISPs are bundling TV and Internet services. The average American watches nearly 35 hours of television a week (Nielsen, 2014). With medium quality stream of Netflix transfers of about 700 MB each hour, the average viewer would watch over 100 GB of standard definition video a month; when one looks at high definition (HD) quality content, that usage number can increase by well over 300%. In July, 2011 Bell executive Mirko Bibic admitted: “No single user or wholesale customer is the cause of congestion” (Lasar, 2011), yet at the same time, the reason given to the regulatory authority for the continuance of this business practice was ostensibly to reduce network congestion. Then, in 2013, Michael Powell, the former Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Chairman who went on to become president of the National Cable and Telecommunications Association, acknowledged that the function of data caps was monetisation of traffic (Bishop, 2013). A survey of ISPs globally found 45% of companies offer at least one application that does not incur data charges, and the specifics of these deals differ between ISPs (Morris, 2014).

At the same time, ISPs are entering private arrangements with content providers and applications that would let those services bypass data caps—a business practice often termed “zero rating” (because use of that service has zero impact on your broadband usage meter). This practice is increasingly prevalent with mobile operators who otherwise restrict data use to under 10 GB a month. In the U.S., AT&T launched a “Sponsored Data” programme to allow partners, such as game development companies and advertisers, to offer free content to their customers (AT&T, 2014); meanwhile, T-Mobile offers free data for certain music applications (T-Mobile, 2014). However, the implications for Digital Craftspersonship is the establishment of a new barrier for new market entrants. Data caps coupled with zero-rating completely undermines network neutrality and end-user control over what content they wish to consume by creating content tiers and complex (hidden) pricing structures. And yet, this growing practice does not, as of the June 2015 FCC rules, run afoul of existing U.S. law. Internationally, this practice is rapidly growing (although, in 2014, Chile announced that zero-rating would not be allowed; in April 2015, India announced that zero rating would be frowned upon—and in February 2016, that it was an illegal practice) (Meyer, 2014; Wall, 2015; Hempel, 2016).

Data caps present a number of policy challenges that are currently being discussed at the FCC and Federal Trade Commission (FTC) in the U.S., and serve as deterrents to universal broadband adoption, thus conflicting with federal efforts to increase broadband adoption. Likewise, data caps directly undermine the shift toward cloud-based (as opposed to local/desktop) computing by creating additional de facto tariffs for data transfers (and potentially resulting in overage charges or even the disconnection of services) (Singel, 2011). Additionally, data caps suppress the use of broadband connections for accessing over-the-top video services like Netflix and YouTube (and any other bandwidth-intensive service or application), presenting a potential barrier to competition that deserves additional scrutiny when ISPs are already offering their own video content. However, the FCC continues to allow this rent-seeking business practice (Brodkin, 2015) and mobile data caps are becoming normalised in Europe and the U.S.

Devices: From coffee makers to John Deere tractors

The widespread introduction of standardised personal computers in the 1980s helped make computing more accessible. Pre-packaged, standardised components meant users no longer needed to solder their own boards and created a platform supporting a market for third-party software that could run on these new platforms (Zittrain, 2008). And for much of the past 30+ years, PCs have been a neutral medium that would run whatever software they were capable of running and connect to whatever network you plugged them into. However, as the following examples underscore, in recent years, while computational capacity has been built into an array of consumer devices, these new digital ecosystems have become vectors of control, rather than interoperability, extensibility and craftspersonship.

Two cases illustrate how computers can control everyday objects like coffee makers and tractors, both of which use the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) as means to justify severe limits on how consumer goods can be used. Introduced in 1998, the DMCA made circumventing digital rights management (DRM), regardless of the intention of this circumvention, illegal (Lessig, 2002). When applied to consumer goods, this effectively redefines ownership of everything from vehicles and coffee machines (i.e., just because you own that device, no longer grants you the right to do with it as you please), making even something as obvious as fixing something that is broken a potential felony.

During the 1990s, Green Mountain Coffee Roasters collaborated with Keurig to sell a single-serve, pod-based coffee brewing machine, a partnership that facilitated both hardware and coffee pod (k-cup) sales. Green Mountain Coffee Roasters experienced remarkable growth and ended up purchasing Keurig. Meanwhile, the sale of brewers and k-cups more than tripled in recent years, from earning US$ 1.2 billion in 2010 to US$ 4 billion by 2014 (McGinn, 2011; Dzieza, 2015). The popularity of the pod-based brewing system allowed Green Mountain Coffee Roasters to license the pod to other coffee roasters, while other coffee companies sold pods independently. However, in 2014, Green Mountain Coffee Roasters, renamed Keurig Green Mountain, integrated DRM into the 2.0 version of their k-cups. These new machines included an infra-red scanner that would detect special ink markings on Keurig coffee pods and would cause the machine to actually fail to work if users attempted to brew “unlicensed coffee pods” in these “new-and-improved” Keurig machines (Dzieza, 2014). By incorporating DRM, Keurig leveraged its control over your coffeemaker to restrict the downstream market of coffee.

The release of DRM coffee proved to be a poor business decision, in part because Keurig 2.0 machines not only locked out competitors coffee pods, but also Keurig’s own 1.0 pods (and the Keurig refillable pod), resulting in a steep decline in sales (Dzieza, 2015). In May 2015, following a 10% decline in share price, Keurig acknowledged the error in forcing consumers to purchase single-use pods and announced a plan to brew unlicensed coffee brands (Geuss, 2015). However, their change of heart was laced with language that would seem to undermine the initial “win” (Barrett, 2015)—Keurig is not planning to remove the DRM, but rather, to make licensing of DRM-equipped k-cups more widespread (Kline, 2015). Ensuring that your choice of coffee will be prescribed, not solely by your own proclivities, but mediated through the licensure practices of the manufacturer of our coffee maker. Meanwhile, most consumers remain completely unaware that their coffee machines are being built to prescribe what coffee you can brew in them.

Keurig is far from the only company seeking to incorporate DRM and use copyright protection measures as a means to control the sale of add-on services or products. For example, new tractors, such as those from John Deere, lock end-users out of making repairs or modifications via both technical limitations and end-user acceptable use policies. Likewise, more and more new cars have Electronic Control Units (ECUs) that prescribe everything from powertrain operations to the battery management. Access to the ECU software is required to run diagnostics on the computer controlling your car engine and for modifying the car to achieve better gas mileage. However, these types of modifications—the digital variation of tinkering on your own car—are illegal on many of these vehicles.

As Benkler writes, the result is that the DMCA favours “giving the copyright owner a power to extinguish the user’s privileged uses” (Benkler, 1999: 421). Although the U.S. Copyright Office conducts a triennial review of DMCA exemptions, companies actively defend their locked-down products and, in doing so, insist consumers do not fully own what they have purchased (Bartholomew, 2015; Lightsey and Fitzgerald, 2015). John Deere defends their own practices by arguing that consumers who purchase their tractors “cannot properly be considered the ‘owner’ of the vehicle software” (Bartholomew, 2015). General Motors also states that end-users merely license the software running their car (Lightsey and Fitzgerald, 2015). While the traditional mechanical craftsperson could repair their own tractor, the 21st Century farmers are increasingly prevented by law from doing so.

Applications: WWW vs. Facebook

In 1990, Tim Berners-Lee began distributing his innovative new scheme to “link” pages of content over a shared computer network. His work, including the now-ubiquitous hypertext transport protocol (HTTP), became the foundation for the World Wide Web. Offered without patent or fee for use, HTTP and HTML allowed digital craftswomen to develop webpages for news, video sharing, search and social media. The Web became the “killer application” for the Internet—the essential application that drove mainstream adoption. However, as with any powerful tool, the liberatory potential for the application is often concomitant with an equally oppressive potential trajectory. While Mosaic and later graphical web browsers like Netscape, Internet Explorer, Firefox and Chrome make the Web accessible over the open Internet, applications can also constrain the user experience in both obvious and remarkably subtle ways.

In 2010, Facebook launched Facebook Zero, a text-only zero-rated walled garden used by partnering telecom carriers. Over the next three years, 10% of Facebook’s billion+ active users used FaceBook Zero (Russell, 2013). In August 2013, Facebook launched Internet.org, a zero-rated application whose initial goal was “to make Internet access available to the two-thirds of the world who are not yet connected, and to bring the same opportunities to everyone that the connected third of the world has today” (Facebook, 2013). Internet.org was a partnership with Facebook, Ericsson, MediaTek, Nokia, Opera, Qualcomm and Samsung and first rolled out with Airtel in Zambia in 2014 (Cooper, 2014).

However, the Internet.org app is very different that the Internet and the Web. While the World Wide Web offers a range of accessible information limited only by the pages end users create, the Internet.org application reduces the network stream to a trickle and offers only a limited range of pages and applications. In Zambia, the services bundled in the launch included AccuWeather, Go Zambia Jobs, Wikipedia, and Facebook. These pages offer services to users, but are such a limited set of options that they more resemble channels on cable television, rather than anything even approaching the Internet. Furthermore, this limited set of services is not even the same as the non-zero-rated versions and fails to provide the same generative potential that Zittrain ascribes to the Web (Zittrain, 2008). Internet.org is an application-based portal to information channels, an Internet experience mediated by a corporate consortium, rather than end users themselves. This is the obvious difference, but it is also the case that Facebook on Facebook Zero is actually different than the Facebook people experience when they access the platform over uncensored Internet connections. Unbeknownst to most people, Facebook Zero’s Facebook is actually stripped of much of its rich content (e.g., pictures, videos)—making for a resource-poor variant that, by Facebook’s own estimate, is passed off to hundreds of millions of the world’s poor as “separate, but equal”.

In May 2015, Mark Zuckerberg, co-founder of Facebook and Internet.org, announced the launch of an Internet.org platform that would allow developers to offer pages or services via a zero-rating Facebook Zero platform. Opening Internet.org is widely seen as positive step to providing more connectivity to users; however, channelling the “Internet” experiences of the world’s poor through a gatekeeper application is not a good option for expanding Digital Craftspersonship—it is more of a bait-and-switch business practice that will eventually leave billions on the wrong side of a new, subtle, but very real, digital divide whereby the range of functionality offered by their Internet service is a pale approximation of what many of the world’s richer constituencies have.

Not all countries have given Internet.org a positive reception. Facebook launched Internet.org (later rebranded as “Free Basics”) in India in February 2015 through a partnership with Reliance Communications (Facebook, 2015). At launch, the service provided access to 38 websites and services in six Indian states. Following this rollout, Kiran Jonnalagadda, founder of HasGeek, a hacker convening in Bangalore, India, helped launch a campaign to oppose Internet.org in India. The #SaveTheInternet campaign directed participants to email the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) regarding their questionnaire “Regulatory Framework for Over-the-top (OTT) services / Internet services and Net Neutrality”. In response to the growing public outcry, in April 2015, Indian companies began pulling out of Internet.org and TRAI asked Reliance Communications to cease offering Free Basics in December 2015 (Doval, 2015). The final trajectory of Facebook’s Free Basics is still unknown, but what is clear is that there is no current plan to offer actual Internet connectivity.

Content: Remixes and political speech

Networked technologies have supported new paradigms of information dissemination, including what Castells describes as mass-self communication, and the growth of independent content producers (Castells, 2010). The role of individual content production has is an important evolution in collective action and contentious political debate (Bimber et al., 2012; Bennett and Segerberg, 2013; Milan, 2015). From YouTube to Tumblr, and from SoundCloud to WordPress, a host of websites and services support individual uploads of self-produced images, text, videos and multi-media, creating a rich environment of personal, yet publicly-hosted information that is now a dominant component of people’s everyday Internet use. However, commercial motivations and legal mandates are exerting more and more influence on how these websites are built, and are rapidly shifting individuals’ “ownership” over their postings to central control over people’s personal content.

The DMCA, which John Deere and GM are using to restrict even the most basic device-level craftspersonship on “owners’” vehicles, actively restricts access to key diagnostic software and even includes a framework for removing personal content from websites. Under the DMCA, U.S.-based websites can be held liable for hosting copyrighted material if the offending material is not removed after receiving an infringement claim, and most online forums abide by these take-down notices, even when they are clearly bogus or otherwise target perfectly legal content. In essence, take-down is automatic, with creators of content “guilty until proven innocent”.

The DMCA is most often used by automated “take-down notice mills” that are creating millions of notices with next to zero fact-checking for fair use (and other safe harbours) and often are almost always complied with with no actual human review. As Seltzer writes, “The DMCA safe harbors may help the service provider and the copyright claimant, but they hurt the parties who were absent from the copyright bargaining table” (Seltzer, 2010: 177). And this doesn’t just impact “the little guys”. During the 2008 U.S. Presidential elections, Republican nominee Senator John McCain had videos removed from YouTube, including content from newscasts that were removed after YouTube received DMCA from news organisations (Sohn and McDiarmid, 2010). In April 2015, U.S. Senator Rand Paul announced his candidacy for the Republican presidential nomination in the United States. His announcement video was automatically removed by YouTube’s copyright Content ID system because the video included clips from John Rich’s 2009 song Shuttin’ Detroit Down (Bump, 2015). And even professor Lawrence Lessig has had YouTube videos of his lecture explaining examples of fair use removed via take-down notice that wrongfully claiming copyright infringement (Andy, 2014).

The DMCA has also been abused in efforts to silence critique. Benkler describes how ATM and election machine manufacturer Diebold forced students at Swarthmore University to remove emails that documented the company’s internal concerns over the security of their voting machines (Benkler, 2006). A decade later, in 2015, News Corp. sent a DMCA request to First Look media including an image of the front page of the Sunday Times in a critique of an article published on that news site (Mullin, 2015).

By contrast, open content can be remixed. For example, an Anonymous cell in Hamburg Germany shared a 2010 video raising concerns about the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement under a Creative Commons license specifically to avoid DMCA takedowns of later adaptations or mirrors (Losey, 2014). Around the globe, Creative Commons is being utilised as a licensing framework that allows content creators to choose to retain some rights, while granting permissionless rights to others, such as reuse or remixing. The license ensured that mirrored uploads of the original Anonymous mashup were perfectly legal (Anonymous Germany, 2012); but even then, DMCA is often used to erode this obvious legal protection. For example, in 2012, NASA uploaded video of their Mars Rover landing on Mars. NASA’s video is public domain and was also used by commercial news services, one of which then issued a DMCA takedown request on NASA’s original upload (Pasternack, 2012). Indeed, law professor and Creative Commons co-founder Lessig acknowledges the licensing system is “a step to rational copyright reform, not itself an ultimate solution” (Lessig, 2008: 279).

Cultural production, including remixing, is a craft requiring modest technical acumen, but well pre-dates the Internet. Artists certainly also created and shared audio and video in the pre-YouTube era. For example, Swedish remix artist Johan Söderberg started his “Read My Lips” series of videos editing clips of world leaders to look like they are singing pop songs as a form of political critique beginning in 2001 (McIntosh, 2012), and the popular satirical news programme The Daily Show frequently uses reappropriation of news commentary and statements. From fandom, such as Anime Music Videos (Knobel and Lankshear, 2008; Ito, 2010), to political appropriation (McIntosh, 2012), and participation in memes (Castells, 2012; Bennett and Segerberg, 2013), content production allows individuals to participate in shared communities and cultural dialogue.

The extent that the Internet can support individual cultural production has been a crucially important component of digitally-mediated political deliberation, both through individual action and as an organising tactic. The “We are the 99%” meme helped grow Occupy Wall Street protests in New York into a global cultural phenomenon. Bennett and Segerberg describe how the Occupy meme “quickly traveled the world via personal stories and images shared on social networks such as Tumblr, Twitter, and Facebook” (Bennett and Segerberg, 2013: loc. 742). Ganesh and Stohl (2013) documented how the Occupy frame inspired complimentary protests as far away as Wellington, New Zealand. Wolfson (2014) describes how a commitment to open-content publishing and journalism created the foundation of the Indymedia movement, which was the first global foray into citizen journalism that utilised both new digital media production technologies and the Internet as a content-distribution system and open publishing platform. Developing digital literacy to participate in community offers educational opportunities (Knobel and Lankshear, 2008); however, copyright regimes that overstep their legal bounds and often utterly ignore fair use to maximise profits are also stifling freedom of expression and create unnecessary (and occasionally illegal) restrictions to Digital Craftspersonship.

Data: Creation and control

With the growth of the Internet of Things, networked data collection is rapidly moving beyond an individual’s web browsing habits to include a far more panoptic range of devices and behaviours, encompassing everything from wearable fitness trackers like Fitbit, to refrigerators and vehicles. Today, farmers are beginning to use GPS mixed with local field data to automate their tractors (Lowenberg-DeBoer, 2015), and this data is, in turn, being collected by the manufacturers of these tractors for unknown purposes. While collecting and utilising these data can create new economic opportunities and open doors for new innovations, with the locus of control over these data often well outside the hands of the users and owners of these services and devices, these tools are often used to commercialise, rather than empower, digital craftsmen.

In June 2015, fitness tracker device company Fitbit had their initial public offering at US$ 20 per share. Through its wearable fitness device, Fitbit sells the consumer a service: the ability to track data about one’s movements and activities. This service is quite valuable, and currently Fitbit dominates this sector with roughly an 85% market share. By the closing bell on its first day of trading, Fitbit’s shares had increased 50%, achieving a US$ 6 billion market capitalisation on its first day of trading (Driebusch, 2015). Clearly, data collection, processing and sales have created significant economic opportunities and incentives for control.

In 2013, Jeff Leak, an assistant professor in biostatistics at John Hopkins University, began experimenting with his Fitbit data. He quickly realised that his Fitbit was collecting minute-by-minute data; however, access to these data was unavailable to him, but actually limited to Fitbit’s business partners (Leek, 2013). As it turned out, access to his stream is negotiated through third-parties, whose applications are then granted access to Fitbit data streams. Although some digital craftspeople have found that they are able to request personal access by emailing Fitbit (Ramirez, 2014), controlling access to one’s own data stream is often a difficult to impossible proposition. As Fitbit exemplifies, data collected by Internet of Things devices is almost always managed through a command-and-control infrastructure that extracts personal information and stores these data in central repositories controlled by the service/device/applications providers, not the user.

While some form of (usually read-only) access to some of these data is often made available, this access is almost always severely limited, changes over time, and offers an incomplete picture of the extent of tracking these devices are doing. For example, in 2012, Twitter introduced new restrictions on how much data third-party applications could access (Kern, 2012). In doing so, Twitter blocked third-party interfaces, and pushed users to use the official Twitter mobile app, rather than the growing host of more diverse, more user-friendly, feature-rich applications. Likewise, researchers analysing Twitter data were locked out of this newly-exclusive data store as well.

The monetary value of open data in the EU27 was estimated in excess of US$ 40 billion in 2010, and has grown substantially since then (Tinholt, 2013). Globally, McKinsey estimates that data, in open sharable formats, could generate US$ 3-5 trillion in economic growth (Chui et al., 2013). However, emerging end-user computing devices not only have limited data-access interfaces, but the data they collect is increasingly tethered to the device and centralised proprietary storage systems as well.

End-user access to data allows individual entrepreneurship, for example, using granular energy use information to maximise the efficiency of electrical use or driving habits—which, as Nest, a connected thermostat offered from Google, exemplifies, is a growing business model (Olson, 2014). The ability for users to access and utilise our own data allows digital craftsmen to develop and share tools that are built on top of this data layer. Additional applications can combine datasets—for example, from smart meters, in-home appliances and control interfaces—to better match usage to budgets and values. End-user applications could also encrypt and locally store data to increase user privacy and security, an obvious solution to the growing problem of centralised data stores being regularly hacked due to inadequate operational security precautions.

For example, LastPass is a networked password manager that, allows users to login using a master password, rather than dozens of passwords for applications, files and logins across devices. However, because the service centrally stores these passwords LastPass is a honeypot—a desirable target for hackers around the globe. In June 2015, LastPass announced that they had been hacked, and although master passwords are encrypted on user devices locally before being transmitted to a central server, hashes from these passwords were accessed, requiring users to change their master passwords (Siegrist, 2015). Hacks of central data stores are a substantial and growing risk of the Internet of Things. For example, in 2014, Apple’s iCloud service was hacked, leading to the release of nude personal photos of dozens of celebrities; and, in 2012, a Facebook bug enabled some accounts to be accessed without a password.

Computer security expert, Bruce Schneier, frames the relationship between users and tech companies as “Feudal Security”, a concept that builds upon Meinrath’s theory of digital feudalism (Meinrath et al., 2010). Feudal Security highlights the dependency of end-users on the companies that collect, transmit and store their data (Schneier, 2012). Schneier acknowledges that while Feudal Security reduces the cost of technological individual expertise in exchange for implicit corporate trust, at the same time, corporate-only solutions prevent individuals from taking control over their own data (Schneier, 2013).

The political economy of the Internet incentivises the collection of end-user data (Fuchs, 2011b), and companies collaborate willingly and unwillingly with large-scale law enforcement surveillance (Meinrath and Vitka, 2014). After the revelations of the Edward Snowden leaks, the spectre of a government surveillance system that permeates phone calls, emails and stored data became alarmingly real. The economic fallout includes a German company building a US$ 1.2 billion data centre to avoid using US cloud services, and total losses to the U.S. tech industry could reach 25% of the total industry’s market share (Miller, 2014). At the same time, surveillance is generating a global demand for new, user-friendly, secure communications tools. However, the ability to develop tools that secure the data layer requires end-user control of data transmission and cooperation—ideally permission-free access—of the underlying layers that compose these technology stacks. Enclosing the data created from the Internet of Things in corporate-controlled digital ecosystems severely limits the ability of digital craftsmen to develop meaningfully secure protections over their personal data and, inevitably, leads to a world where more and more private information is placed at severe risk.

The future of Digital Craftspersonship

Over the next decade, the number of networked devices is expected to grow by an order of magnitude. By 2015, the Internet connected over eight billion devices around the globe—more than one per person; Cisco projects that by 2020 there will be 6.5 Internet-connected devices for every person on the planet (Evans, 2011). However, the locus of control over networks, devices, applications, content and data will determine the extent that Digital Craftspersonship will continue to thrive. As postulated by Sennet (2008), building creative solutions are an innate human characteristic; however, the integration of computers into everyday objects do not, by default, encourage this fundamental human drive. As this paper explicates, whether due to financial or political interests, centralised-by-design technological architectures are constraining innovation in ways that are harmful, not helpful.

The framework we present serves to illustrate that the potential for constraint is not limited to specific actors, but that any actor within the interconnected technologies that supports networked communications technologies, can leverage control over one layer to exert control over the entire technology stack. This paper provides a conceptual model for understanding the Internet of Things as a network of mediated relationships in which the architectures and controls over the corresponding layers of networked systems directly impact the range of freedoms experienced by end users. Each layer offers great potential for innovation, but also concomitant risk when appropriated by centralised, proprietary systems.

Without regulatory constraints, ISPs will continue to leverage control over network infrastructure to explore new ways to monetise Internet traffic. By definition, these ISPs are constraining how an Internet connection can be utilised (as examples, acceptable use policies that ban home servers or stream video, or exempt a particular service offering from a data cap and discriminating against other functional equivalents). At the same time, the addition of computing technology within a coffeemaker does not guarantee new benefits for consumers, but instead is being used to restrict what types of coffee can be used (a sordid “function” that customers are then unknowingly having to pay for in the purchase price of this equipment). Historically, the Internet has been as a platform for permissionless innovation; this paper documents the increasing array of commercialisation tactics that fundamentally reshapes the innovative potential of computer mediated technologies to lock down, control and surveil everyday activities.

Digital Craftspersonship is an ideal that can serve as a benchmarch for public policy decision making, especially for policy makers that want to promote the Internet as a platform for economic opportunity. Legislation and regulations that impact each layer of a technology stack should be evaluated to determine whether they increase or reduce the potential for craftspersonship. The establishment of network neutrality rules in the United States, and resistance to an application-restricted “Internet” in India, demonstrate positive steps forward for preserving network-layer craftpersonship. However, the use of copyright to shift the concept of “ownership” of everyday goods—from cars to coffeemakers—illustrates how companies are exerting control over goods in fundamentally new ways, necessitating updates to traditional consumer protections. Additionally, control of personal information continues to be a growing policy predicament.

If the agility and independence of any one technology layer is subsumed by dominant market players, the overall economic value of that layer will be dramatically decreased and future innovative potential will be likewise curtailed. A future that protects end-user innovation and the public good must take this into account, especially as we enter an Internet of Things era. This includes the ability to use and innovate without the permission of the network (Lessig, 2002), as well as preventing one layer from foreclosing on the generativity of another (Zittrain, 2008). The extent that corporate control is allowed to encroach upon the potential for Digital Craftspersonship will determine the parameters of “ownership” in the 21st Century.

Entrepreneurs, policy makers and careful and critical observers must look beyond their surface-level understanding of technology and interrogate the technological underpinnings of contemporary and future digital technologies. The overarching positive and negative repercussions of technological innovations are increasingly not silo-ised, but can only be understood in relation to the larger digital ecosystem in which they reside. We provide a parsimonious framework for understanding how the politics within and amongst technological layers of networked systems change the relationship between users, owners and digital technology. This framework focuses on the relationship between users and the networked communications tools they utilise. And the future of Digital Craftspersonship will pit the liberatory potential of new technologies against corporate forces seeking to create feudalistic digital ecosystems; with the outcome determining whether we have the ability to innovate and tinker, or whether we will become digital serfs facing an ever-more-oppressive panoptic and data extractive networked world.

End Note

[1] In cases like the citizens’ band (CB), spectrum is set aside for amateur use, or according to “Part 15” rules that allow some public wireless devices, such as garage door openers and microwave ovens, to operate in unlicensed spectrum. See Bennett Z. Kobb, Wireless Spectrum Finder: Telecommunications, Government and Scientific Radio Frequency Allocations in the US 30 MHz – 300 GHz (McGraw-Hill 2001), and National Telecommunications and Information Administration, Manual of Regulations and Procedures for Federal Radio Frequency Management (Redbook) (Washington: US Government Printing Office, 2008).

References

Anderson, C. (2008) The Long Tail: Why the Future of Business is Selling Less of More. Revised Edition. New York: Hachette Books.

Andy (2014) “Tumblr Complies With DMCA Takedown Requests From A Self-Proclaimed Future-Alien From Another Planet”. Torrent Freak, 23 June. Available at: https://www.techdirt.com/articles/20150618/14264131389/tumblr-complies-with-dmca-takedown-requests-self-proclaimed-future-alien-another-planet.shtml (accessed on 30 June 2015).

Anonymous Germany (2012) “Anonymous – Was ist ACTA? – #StopACTA [german sync]”. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9LEhf7pP3Pw (accessed on 30 June 2015).

Ashton, K. (2009) “That ‘Internet of Things’ Thing”. RFiD Journal 22(7): 97-114.

AT&T (2014) “AT&T Introduces Sponsored Data for Mobile Data Subscribers and Businesses”. Available at: http://www.att.com/gen/press-room?pid=25183&cdvn=news&newsarticleid=37366&mapcode= (accessed on 30 June 2015).

Barrett, B. (2015) “Keurig’s My K-Cup Retreat Shows We Can Beat DRM”. Wired, 8 May. Available at: http://www.wired.com/2015/05/keurig-k-cup-drm/ (accessed on 30 June 2015).

Batholomew, D. (2015) Long Comment Regarding a Proposed Exemption Under 17 U.S.C. 1201 United States Copyright Office, Library of Congress, Docket No. 2014-07 Proposed Class 21: Vehicle Software – Diagnosis, Repair, or Modification. Available at: http://copyright.gov/1201/2015/comments-032715/class%2021/John_Deere_Class21_1201_2014.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2015).

Benkler, Yochai (1999) “Free as the Air to Common use: First Amendment Constraints on Enclosure of the Public Domain”. NYU Law Rev. 74: 354.

——— (2006) Wealth of Networks: How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Bennett, W. L. and A. Segerberg (2013) The Logic of Connective Action: Digital Media and the Personalization of Contentious Politics. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bimber, B. A,, A. J. Flanagin and C. Stohl (2012) Collective Action in Organizations: Interaction and Engagement in an Era of Technological Change. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bishop, B. (2013) “Former FCC Chairman admits data caps aren’t about preventing network congestion”. The Verge, 18 January. Available at: http://www.theverge.com/2013/1/18/3892410/former-fcc-chairman-admits-data-caps-arent-about-preventing-network-congestion (accessed on 30 June 2015).

Brodkin, J. (2015) “AT&T still throttles unlimited data, and FCC isn’t promising to stop it”. Ars Technica, 12 March. Available at: http://arstechnica.com/business/2015/03/att-still-throttles-unlimited-data-and-fcc-isnt-promising-to-stop-it/ (accessed on 30 June 2015).

Bump, P. (2015) “YouTube’s copyright system has taken Rand Paul’s presidential announcement offline”. The Washington Post, 7 April. Available at: http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/the-fix/wp/2015/04/07/youtubes-copyright-system-has-taken-rand-pauls-presidential-announcement-offline/ (accessed on 30 June 2015).

Burns, K. (2003) TCP/IP Analysis & Troubleshooting Toolkit. John Wiley & Sons.

Cahnman, W. J. (1965) “Ideal Type Theory: Max Weber’s Concept and Some of Its Derivations”. The Sociological Quarterly 6(3): 268-280.

Castells, M. (2009) The Rise of the Network Society: The Information Age: Economy, society and culture, Vol. 1. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers

——— (2010) The Power of Identity: The Information Age: Economy, society and culture, Vol. II. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

——— (2012) Networks of Outrage and Hope. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Chui, M., P. Groves, D. Farrell, S. Van Kuiken and E. A. D. J. Manyika (2013) Open Data: Unlocking Innovation and Performance with Liquid Information. McKinsey & Co.

Cooper, P. (2014) “Facebook finally rolls out Internet.org, bringing free Internet to Africa”. IT Pro Portal, 31 July. Available at: http://www.itproportal.com/2014/07/31/facebook-finally-rolls-out-internetorg-bringing-free-internet-to-africa (accessed on 30 June 2015).

De Filippi, P. and F. Tréguer (2014) “Expanding the Internet Commons: The Subversive Potential of Wireless Community Networks”. Journal of Peer Production 6: 1-11.

Deering, S. (2001) “Watching the Waist of the Protocol Hourglass”. IETF 51. Available at: http://www.iab.org/wp-content/IAB-uploads/2011/03/hourglass-london-ietf.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2015).

Doval, P. (2015) “Put FB’s Free Basics service on hold, TRAI tells Reliance Communications”. Times of India, 23 December. Available at: http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/tech/tech-news/put-fbs-free-basics-service-on-hold-trai-tells-reliance-communications/articleshow/50290490.cms?from=mdr (accessed on 14 January 2016).

Driebusch, C. (2015) “Fitbit IPO Prices at $20 a Share, Above Expectations”. The Wall Street Journal, 17 June. Available at: http://www.wsj.com/articles/fitbit-ipo-prices-at-20-a-share-above-expectations-1434582147 (accessed on 30 June 2015).

Dzieza, J. (2014) “Inside Keurig’s plan to stop you from buying knockoff K-Cups”. The Verge, 30 June. Available at: http://www.theverge.com/2014/6/30/5857030/keurig-digital-rights-management-coffee-pod-pirates (accessed on 30 June 2015).

——— (2015) “Keurig’s attempt to ‘DRM’ its coffee cups totally backfired”. The Verge, 5 February. Available at: http://www.theverge.com/2015/2/5/7986327/keurigs-attempt-to-drm-its-coffee-cups-totally-backfired (accessed on 30 June 2015).

The Digital Millennium Copyright Act (1998) Pub. L. No. 105–304, 112 Stat. 2860, 28 October. Available at: www.copyright.gov/legislation/dmca.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2015).

European Commission (n.d.) “The Internet of Things”, in Digital Agenda For Europe. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/digital-agenda/en/internet-things (accessed on 30 June 2015).

Evans, D. (2011) “The Internet of Things: How the Next Evolution of the Internet is Changing Everything”. CISCO White Paper. Available at: http://www.cisco.com/web/about/ac79/docs/innov/IoT_IBSG_0411FINAL.pdf (30 June 2015).

Facebook (2013) “Technology Leaders Launch Partnership to Make Internet Access Available to All”. Press Release, 21 August. Available at: https://newsroom.fb.com/news/2013/08/technology-leaders-launch-partnership-to-make-internet-access-available-to-all/ [30 June 2015].

——— 2015, Internet.org App Now Available in India, Press Release, 10 February. Available from: http://newsroom.fb.com/news/2015/02/internet-org-app-now-available-in-india/ (accessed on 30 June 2015).

Federal Trade Commission (2015) “Internet of Things—Privacy and Security in a Connected World”. Available at: https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/reports/federal-trade-commission-staff-report-november-2013-workshop-entitled-internet-things-privacy/150127iotrpt.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2015).

Flanagin, A. J., C. Flanagin and J. Flanagin (2010) “Technical code and the social construction of the internet”. New Media & Society 12(2): 179-196.

Fuchs, C. (2011a) Foundations of Critical Media and Information Studies. Taylor & Francis.

——— (2011b) “New Media, Web 2.0 and Surveillance”. Sociology Compass 5(2): 134-147.

Galloway, A. R. (2004) Protocol: How Control Exists After Decentralization. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Ganesh, S. and C. Stohl (2013) “From Wall Street to Wellington: Protests in an era of digital ubiquity”. Communication Monographs 80(4): 425-451.

Geuss, M. (2015) “Keurig says it was wrong to force users to buy single-serving pods”. Ars Technica, 7 May. Available at: http://arstechnica.com/business/2015/05/keurig-stock-drops-10-percent-says-it-was-wrong-about-drm-coffee-pods/ (accessed on 30 June 2015).

Hempel, J. (2016) “India Bans Facebook’s Basics App to Support Net Neutrality”. Wired Magazine, 8 February. Available at: http://www.wired.com/2016/02/facebooks-free-basics-app-is-now-banned-in-india (accessed on 11 February 2016).

Ito, M. (2010) “The rewards of non-commercial production: Distinctions and Status in the Anime Music Video Scene”. First Monday 15(5).

Jasanoff, S. (2006) “Technology as a Site and Object of Politics”, in R. E. Goodin and C. Tilly (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Contextual Political Analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 745-763.

Katz, R. (2014) “Assessment of the Economic Value of Unlicensed Spectrum in the United States, Telecom Advisory Services, LLC., Report, February. Available at: http://www.wififorward.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Value-of-Unlicensed-Spectrum-to-the-US-Economy-Full-Report.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2015).

Kern, E. (2012) “Game changer: Twitter rolls out expected restrictions to API use”. GigaOm, 16 August. Available at: https://gigaom.com/2012/08/16/twitter-rolls-out-expected-restrictions-to-api-use/ (accessed on 30 June 2015).

Kline, D. B. (2015) “What Keurig’s New Stance On DRM Means for Unlicensed K-Cups”. Motley Fool, 11 May. Available at: http://www.fool.com/investing/general/2015/05/11/what-keurigs-new-stance-on-drm-means-for-unlicense.aspx (accessed on 30 June 2015).

Knobel, M. and C. Lankshear (2008) “Remix: The Art and Craft of Endless Hybridization”. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy 52(1): 22-33.

Lasar, M. (2011) “Metered billing: It’s a lack of competition, not congestion”. Ars Technica, 12 July. Available at: http://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2011/07/metered-billing-its-a-lack-of-competition-not-congestion/ (accessed on 30 June 2015).

Leek, J. (2013) “Fitbit, why can’t I have my data?” Jeff Leek: Blog, 2 January. Available at: http://simplystatistics.org/2013/01/02/fitbit-why-cant-i-have-my-data/ (accessed on 30 June 2015).

Lessig, L. (2002) The Future of Ideas: The Fate of the Commons in a Connected World. London: Vintage Books.

——— (2006) Code Version 2.0. New York: Basic Books.

——— (2008) Remix: Making Art and Culture Thrive in the Hybrid Economy. New York: Penguin Books.

Levy, S. (2001) Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution. New York: Penguin Books.

Lightsey, H. M. and A. Q. Fitzgerald (2015) “Comments of General Motors LLC, United States Copyright Office, Library of Congress, Docket No. 2014-07 Proposed Class 21: Vehicle Software – Diagnosis, Repair, or Modification”. Available at: http://copyright.gov/1201/2015/comments-032715/class%2021/General_Motors_Class21_1201_2014.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2015).

Losey, J. (2014) “The Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement and European Civil Society: A Case Study on Networked Advocacy”. Journal of Information Policy 4: 205-227.

——— (2015) “The Locus of Control in Networked Communications: Implications for Collective Action”. Paper presented at the International Communications Association Annual Conference: Communications Across the Lifespan, 21-25 May, San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Lowenberg-DeBoer, J. (2015) “The Precision Agriculture Revolution”. Foreign Affairs 94(3): 105-112.

Manyika, J., M. Chui, D. Farrell, S. Van Kuiken, P. Groves and E. A. Doshi (2014) “Open Data: Unlocking Innovation and Performance with Liquid Information”. McKinsey & Company. Available at: http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/business_technology/open_data_unlocking_innovation_and_performance_with_liquid_information (accessed on 30 June 2015).

McChesney, R. W. (2013) Digital Disconnect: How Capitalism is Turning the Internet Against Democracy. New York: The New Press.

McGinn, D. (2011) “The Buzz Machine”. The Boston Globe, 7 August. Available at: http://www.boston.com/business/articles/2011/08/07/the_inside_story_of_keurigs_rise_to_a_billion_dollar_coffee_empire/?page=6 (accessed on 30 June 2015).

McIntosh, J. (2012) “A History of Subversive Remix Video before YouTube: Thirty Political Video Mashups Made between World War II and 2005”. Transformative Works and Cultures 9.

Meinrath, S. D. and S. Vitka (2014) “Crypto War II”. Critical Studies in Media Communication 31(2): 123-128.

Meinrath, S. D., J. Losey and B. Lennett (2013) “Internet freedom, nuanced digital divides, and the Internet craftsman”, in M. Ragnedda and G. Muschert (eds.) The Digital Divide: The Internet and Social Inequality in International Perspective. Routeledge, pp. 309-315.

Meinrath, S. D., J. Losey and V. W. Pickard (2010) “Digital Feudalism: Enclosures and Erasures from the Digital Rights Management to the Digital Divide”. Commlaw Conspectus 19: 423–479.

Meyer, D. (2014) “In Chile, mobile carriers can no longer offer free Twitter, Facebook or WhatsApp”. GigaOm, 28 May. Available at: https://gigaom.com/2014/05/28/in-chile-mobile-carriers-can-no-longer-offer-free-twitter-facebook-and-whatsapp/ (accessed on 30 June 2015).

Milan, S. (2015) “From Social movements to Cloud Protesting: The Evolution of Collective Identity”. Information, Communication and Society 18(8): 1–14.

Miller, C. C. (2014) “Revelations of N.S.A. Spying Cost U.S. Tech Companies”. The New York Times, 21 March. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/22/business/fallout-from-snowden-hurting-bottom-line-of-tech-companies.html (accessed on 30 June 2015).

Minne, J. (2013) “Data Caps: How ISPs are Stunting the Growth of Online Video Distributors and What Regulators Can Do About It”. Fed. Comm. LJ 65: 234-260.

Morris, A. (2014) “Report: 45% of operators now offer at least one zero-rated app”. Fierce Wireless, 15 July. Available at: http://www.fiercewireless.com/europe/story/report-45-operators-now-offer-least-one-zero-rated-app/2014-07-15 (accessed on 30 June 2015).

Mosco, V. (1996 ) The Political Economy of Communication. Sage.

Mullin, J. (2015) “The Sunday Times sends DMCA notice to critics of Snowden hacking story”. Ars Technica, 16 June. Available at: http://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2015/06/sunday-times-sends-dmca-notice-to-critics-of-snowden-hacking-story/ (accessed on 30 June 2015).

Nielsen (2014) “Content is King, But Viewing Habits Vary by Demographic”. Available at: http://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/news/2014/content-is-king-but-viewing-habits-vary-by-demographic.html (accessed on 30 June 2015).

Olson, P. (2014) “The Quantified Other: Nest And Fitbit Chase A Lucrative Side Business”. Forbes, 17 April. Available at: http://www.forbes.com/sites/parmyolson/2014/04/17/the-quantified-other-nest-and-fitbit-chase-a-lucrative-side-business/ (accessed on 30 June 2015).

Palfrey, J. and J. Zittrain (2011) “Better data for a better Internet”. Science 334(6060): 1210-1211.

Pasternack, A. (2012) “NASA’s Mars Rover Crashed Into a DMCA Takedown”. Motherboard, 6 August. Available at: http://motherboard.vice.com/blog/nasa-s-mars-rover-crashed-into-a-dmca-takedown (accessed on 30 June 2015).

Pélissié du Rausas, M., J. Manyika, E. Hazan, J. Bughin, M. Chui and R. Said (2011) “Internet Matters: The Net’s Sweeping Impact on Growth, Jobs, and Prosperity”. McKinsey & Company. Available at: http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/high_tech_telecoms_internet/internet_matters (accessed on 30 June 2015).

Ramirez, E. (2014) “How to Download Minute-by-Minute Fitbit Data”. Quantified Self, 26 September. Available at: http://quantifiedself.com/2014/09/download-minute-fitbit-data/ (accessed on 30 June 2015).

Russell, J. (2013) “Facebook’s ‘Every Phone’ app for feature phones passes 100 million monthly active users”. The Next Web, 22 July. Available at: http://thenextweb.com/facebook/2013/07/22/facebooks-every-phone-app-for-feature-phones-passes-100-million-monthly-active-users/ (accessed on 30 June 2015).

Saltzer, J. H., D. P. Reed and D. D. Clark (1981) “End-to-End Arguments in System Design”, in Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems, Paris, France. IEEE Computer Society, pp. 509-512.

Schneier, B. (2012) “Feudal Security”. Schneier on Security, 3 December. Available at: https://www.schneier.com/blog/archives/2012/12/feudal_sec.html (accessed on 30 June 2015).

——— (2013) “You Have No Control Over Security on the Feudal Internet”. Harvard Business Review, 6 June. Available at: https://hbr.org/2013/06/you-have-no-control-over-s (accessed on 30 June 2015).

——— (2015) Data and Goliath: The Hidden Battles to Capture Your Data and Control Your World. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Schumpeter, J. (1942) “Creative destruction”, in Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. New York: Harper, pp. 82-85.

Sennett, R. (2008) The Craftsman. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Seltzer, W. (2010) “Free Speech Unmoored in Copyright’s Safe Harbor: Chilling Effects of the DMCA on the First Amendment”. Harvard Journal of Law and Technology 24(1): 171-232.

Siegrist, J. (2015) “LastPass Security Notice. 15 June 2015, Updated 16 June 2015”. LastPass Blog. Available at: https://blog.lastpass.com/2015/06/lastpass-security-notice.html/ (accessed on 30 June 2015).

Singel, R. (2011) “Comcast Bans Seattle Man from Internet for His Cloudy Ways”. Wired, 13 July. Available at: http://www.wired.com/2011/07/seattle-comcast/ (accessed on 30 June 2015).

Sohn, D. and A. McDiarmid (2010) “Campaign Takedown Troubles: How Meritless Copyright Claims Threaten Online Political Speech, Center for Democracy and Technology”. Available at: https://www.cdt.org/files/pdfs/copyright_takedowns.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2015).

Tinholt, D. (2013) “The Open Data Economy: Unlocking Economic Value by Opening Government and Public Data”. Capgemini Consulting. Available at: http://ebooks.capgemini-consulting.com/The-Open-Data-Economy/ (accessed on 30 June 2015).

T-Mobile (2014) “T-Mobile Sets Your Music Free, 18 June 2014”. Available at: http://newsroom.t-mobile.com/news/t-mobile-sets-your-music-free.htm (accessed on 30 June 2015).

Van Schewick, B. (2010) Internet Architecture and Innovation. Cambridge: MIT University Press.

Weber, M. (1947) The Theory of Social and Economic Organization. New York: Oxford University Press.

Winner, L. (1980) “Do Artifacts Have Politics?”, Daedalus 109(1): 121-136.

Wolfson, T. (2014) Digital Rebellion: The Birth of the Cyber Left. University of Illinois Press.

Wu, T. (2011) The Master Switch: The Rise and Fall of Information Empires. New York: Vintage Books.

Zittrain, J. (2008) The Future of the Internet—and How to Stop It. Yale University Press.

James Losey is Doctoral Candidate at the School of International Studies and the Department of Media Studies, Stockholm University. james.losey[a]ims.su.se.

Sascha D. Meinrath is Palmer Chair in Telecommunications at Penn State University.